Psalm 23

The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want

with

CRIMOND

BROTHER JAMES’ AIR (MAROSA)

BELMONT

I. Text: Origins

At the dawn of the Reformation, Protestants in England had prepared a metrical psalter, The Whole Booke of Psalmes (1562), based on the work of Sternhold & Hopkins, and their counterparts in the Church of Scotland adopted a similar psalter, published as The Forme of Prayers . . . with the Whole Psalmes of David in English Meter (1564). Both psalters were published successfully for several decades, but the poetry in them was not highly regarded. Desirous of a smoother rendition of the Psalms, Francis Rous (1580/1–1659), a long-serving member of the English Parliament (1620–1659) and Provost of Eton College (1644–1659), set about to produce a new version. His first attempt was published anonymously as The Booke of Psalmes in English Meeter (Rotterdam: Henry Tutill, 1638). In his preface, he was concerned about the stronghold of the old psalters, and he believed the need for change was undeniable:

Diverse well affected persons have turned [the Psalms] into their own languages, and not only so, but they have turned them also into harmonious measures, that they may be still used as Psalms, that is, as spiritual and heavenly songs. For the advancement of this profitable use, apprehending many years past (which experience hath showed to be a true conjecture), that a form wholly new would not please many, who are fastened to things usual and accustomed (though if psalms of a new form be read before they be sung, there is no hindrance but that they may be presently used, and after a little use will grow familiar; as the former). I assayed only to change some pieces of the usual version, even such as seemed to call aloud, and as it were undeniably for a change.

These being seen, it was desired that they should be increased, which being done, are here subjoined. I doubt not but the reasons of the changes will mostly appear in the changes themselves, and the reader may easily find that the places changed might well receive a change for their cadence or currence, or for some old and abolished words, or, which is more, for agreeing less with the New Translation, yea, with the original itself.[1]

Rous’s stated goal was merely to change or update the “usual version,” and as his rendering of Psalm 23 shows, he consulted both the English and Scottish versions. The English psalter of 1562 used a paraphrase by (probably) Thomas Norton beginning “My shepherd is the living Lord,” which was first printed in Psalmes of David in Englishe Metre (1561). The Scottish psalter of 1564 used a paraphrase by William Whittingham beginning “The Lord is only my support,” which was first printed in One and Fiftie Psalmes of David in Englishe Metre (Geneva, 1556).

In both cases below, the paraphrases are misattributed to Thomas Sternhold. The text in Fig. 1 from 1562 is definitely not by Thomas Sternhold, who was deceased when this text was first printed, which means it would have been produced by either Thomas Norton or John Hopkins; Norton is considered the most likely author for reasons relating to form and style.[2] The text in Fig. 2 from 1564 is credited clearly to Whittingham in other editions.

Fig. 1. The Whole Booke of Psalmes (1562)

Fig. 2. The Forme of Prayers . . . with the Whole Psalmes of David in English Meter (1564).

In the first edition prepared by Rous, The Booke of Psalmes in English Meeter (1638), Psalm 23 began “My shepherd is the living Lord” (Fig. 3), borrowing from Norton, but the second half of his first quatrain borrowed from Whittingham. The rest is based on Whittingham’s text, except for the last quatrain, which is based loosely on Norton.

Fig. 3. The Booke of Psalmes in English Meeter (Rotterdam: Henry Tutill, 1638).

Another edition of Rous’s psalter appeared in 1641; Psalm 23 was unchanged. On 17 April 1643, the collection was officially recognized by the House of Commons in Parliament as suitable for “general use.” In the subsequent 1643 edition, Psalm 23 appeared again without change. On 20 November 1643, the House of Commons ordered the collection to be referred to the Westminster Assembly of Divines for consideration. After a full year, on 27 December 1644, the Assembly of Divines offered their recommendations back to the House of Commons. A greatly altered version, made with the input of Rous, was presented the following year, 14 November 1645:

Whereas the Honorable House of Commons, by an order bearing date November 20, 1643, have recommended the Psalms published by Mr. Rous, to the consideration of the Assembly of Divines, the Assembly has caused them to be carefully perused, and as they are now altered and amended to approve them, and humbly conceive they may be useful and profitable for the Church, if they may be permitted to be publically sung.[3]

After much debate, including arguments in preference of the paraphrases by William Barton (The Book of Psalms in Metre Close and Proper to the Hebrew, 1644, rev. 1645), the revised version of Rous was approved by the House of Commons on 16 April 1646. This was printed as The Psalms of David in English Meeter (London: Miles Flesher, 1646), with the King James (1611) text given in the margins for comparison. In this edition, Rous’s version of Psalm 23 had been overhauled (Fig. 4). Although some lines were arguably improved, the first stanza, in an attempt at accuracy, suffered from structural lapses, with ideas running from one line into another (enjambment). Among the snippets retained from the original paraphrase were the last line of the third verse, the last three lines of the fifth verse, and two lines in the sixth verse.

Fig. 4. The Psalms of David in English Meeter (London: Miles Flesher, 1646).

In spite of being approved by the House of Commons and the Assembly of Divines, it was not confirmed by the House of Lords, which meant it never received the full blessing of the government, and “was not, by statutory enactment, adopted as part of the ‘Uniformity of Worship,’ which was the dream of the age,”[4] and it was thus not broadly embraced by the English public, but it drew interest from members of the Church of Scotland.

Some members of the Assembly of Divines responsible for revising Rous’s psalter were commissioners from the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Among them was Robert Baillie (1602–1662), professor of divinity at the University of Glasgow. Baillie presented the 1646 Psalms of David to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland for consideration on 21 January 1647, using a paper drafted by the Scottish commissioners who had reviewed Rous’s work. A committee was then appointed for further review and revision, initially consisting of John Adamson, Thomas Crawford, John Row, and John Nevay. Adamson was given charge of the first forty psalms. In 1648, another committee of six members was asked to review and revise what had been done.

For this task, the Assembly asked committee members to consult a metrical psalter made by William Mure of Rowallan, a well-respected nobleman and poet in Ayrshire who had completed a manuscript version around 1639 (unpublished, but later included in The Works of Sir William Mure of Rowallan, vol. 2, 1898), and a metrical psalter rendered by Zachary Boyd (The Psalmes of David in Meeter, 1646, rev. 1648), who was minister of the Barony Parish in Glasgow. Concerning Psalm 23, Mure’s influence on the committee’s work is apparent in the wording of the last two lines of verse 4.

Fig. 5. The Works of Sir William Mure of Rowallan, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1898).

Regarding Boyd’s psalter, Baillie felt the paraphrases were overrated, and he believed local interest in them had delayed the final product:

Our good friend, Mr. Zachary Boyd, has put himself to a great deal of pains and charges to make a psalter, but I ever warned him his hopes were groundless to get it received in our churches, yet the flatteries of his unadvised neighbours makes him insist in his fruitless design. The Psalms were often revised and sent to presbyteries. Had it not been for some who had more regard than needed to Mr. Zachary Boyd’s psalter, I think they had passed through in the end of last Assembly.[5]

In spite of Baillie’s misgivings, Boyd’s paraphrase was notably influential on the outcome of Psalm 23. His revised version of 1648 gave voice to the Psalm’s opening lines: “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want / He makes me down to ly.”

Fig. 6. The Psalmes of David in Meeter (Glasgow: Heirs of George Anderson, 1648).

The final draft of the Scottish psalter was approved on 23 November 1649 for publication, with a targeted release date of the first of May, and it was printed as The Psalms of David in Meeter (Edinburgh: Evan Tyler, 1650). In the end, their version of Psalm 23 included language from Thomas Norton, William Whittingham, Francis Rous, members of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, William Mure, Zachary Boyd, and committee members of the General Assembly of the Church (Kirk) of Scotland. The challenge of a paraphrase such as this is in the desire to be faithful to the Scriptures while also making the text sensible and singable in English rhyme. This was often achieved through word inversions (“quiet waters by,” “me comfort still”). Out of all the paraphrases in the 1650 Scottish Psalter, the rendition of Psalm 23 is the most frequently reprinted.

Fig. 7. The Psalms of David in Meeter (Edinburgh: Evan Tyler, 1650).

Sources of the 1650 Scottish Version:

1. Zachary Boyd

2a. Rous / Boyd

2b. Boyd, alt. Scots

2c. Boyd, alt. Scots

3a. Westminster

3b. Westminster

3c. Westminster, alt. Boyd

3d. William Whittingham

4a. Norton, alt. Westminster

4b. Whittingham / Norton

4c. William Mure, alt. Scots

4d. William Mure

5a. Scottish 1650

5b. Whittingham, alt. Rous

5c. Francis Rous, alt. Scots

5d. Whittingham / Rous, alt. Scots

6a. Rouse, alt. Westminster

6b. Francis Rous

6c. Norton, alt. Westminster

6d. Thomas Norton

III. Tunes

Initially, this text would have been sung with any suitable common-meter tune, including the tunes published in The Psalmes of David in Prose and Meeter (1635). In the 20th century, hymnal editors began to settle around a few favored tunes.

1. CRIMOND

Authorship and Origins

The most popular tune in circulation is CRIMOND. The authorship of the tune has been somewhat contentious, involving two competing claims, both with some merit. It was first printed as a single leaflet in the series of Fly Leaf of Psalm and Hymn Tunes in 1871 (no surviving copies could be located), then these were combined into The Northern Psalter and Hymn Tune Book (1872 | Fig. 8) edited by William Carnie. In this instance it was called CRIMOND and credited to David Grant (1833–1893), set to a text by George W. Doane. The preface and index also credited the tune to Grant.

Fig. 8a. The Northern Psalter and Hymn Tune Book (Aberdeen: Lewis Smith, Taylor & Henderson, 1872).

Fig. 8b. The Northern Psalter, Addenda Ed. (Aberdeen: Lewis Smith, Taylor & Henderson, 1877).

Carnie, in a speech delivered to the Aberdeen Burns Club on 25 January 1897 remembered Grant and his contribution in these words:

Mr. David Grant was, in his day, an outstanding figure in musical Aberdeen, and assuredly one of the cheeriest, hail-fellow-well-met comrades of the Burns Club. A fine-browed, broad-chested little man of, say, forty-five at the time spoken of, and notwithstanding a considerable halt in his walk (out of which he used to coin jokes) as active as a schoolboy. He was long a tabacconist at 25 Union Street (head of Shiprow), and go into his shop at any hour of the day you chose you would find him this five minutes busy serving customers, and the next five minutes rapidly scoring “parts” for some of our local instrumental bands or arranging hymn tunes—say, for the Northern Psalter.

“Here,” he said to me one evening, “here, pit that in your bookie,” and he produced the MS of a long-metre tune. Its pleasant movement could be gathered at a glance. . . . He also contributed another catching melody still frequently sung—CRIMOND—so called, I think, at the instance of our friend Mr. Robert Cooper.[6]

Cooper was the precentor at the West Kirk of Aberdeen starting in 1871, a year before the tune was published. Grant’s authorship of the tune was not publicly questioned until almost forty years later, when the Rev. Robert T. Monteith became the parish minister of Crimond, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. In a letter to The Scotsman, 20 September 1948, he indicated some measure of confusion about the authorship had already been circulating in the community:

Shortly after I became parish minister at Crimond in 1909 I was asked by the Revd Dr Kemp, parish minister of Deer—himself an authority on music and a cultured musician—to endeavor to throw some light on the subject. I was fortunate in ascertaining that a sister of the composer of the melody was still alive and, in response to my request, she stated in a letter that her sister, Miss J.S. Irvine, composed the melody and got David Grant, the compiler of The Norther Psalter, to harmonize it for her. She named it after her father’s parish, Crimond, situated on the north-east coast of Aberdeenshire.[7]

The letter by Anna Barbara Irvine (1830–1924), daughter of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Irvine (1804–1884) and sister of Jessie Seymour Irvine (1836–1887), was dated 31 May 1911 and is now preserved in the Aberdeen University Library (MS 2163). It reads:

I shall be happy to tell you all I know about the tune CRIMOND. It was composed by my late sister J.S. Irvine. I have a copy of The Precentor’s Companion and Teacher’s Indicator to the Northern Psalter and Hymn Tune Book by William Carnie, Aberdeen, with tune CRIMOND in it, which was used in Crimond church choir. I think it was William Carnie who got it harmonised by David Grant, as noted in Psalter. We had a splendid choir in Crimond in my father’s time with the late Mr. Clubb as leader. Hoping this information will be of use.[8]

Rev. Monteith’s advocacy notwithstanding, Grant continued to be credited as the sole author in publications of the song, including in the Scottish Psalter 1929 (using a harmonization by T.C.L. Pritchard), in the Scottish Church Hymnary Revised Edition (1927), and in the supporting Handbook to the Church Hymnary with Supplement (1935), edited by James Moffatt and Millar Patrick. Grant’s name was given on sheet music and vinyl discs issued by the famed Glasgow Orpheus Choir and it’s conductor-composer Hugh Roberton in the 1930s and 1940s (more on this below). If there was a local knowledge in Crimond of Irvine’s authorship, the rest of Scotland knew nothing of it.

The tides changed in 1948, when Millar Patrick, based on some unknown prompting and without anything more than local lore, affirmed Monteith’s account, relaying, “The people of the district are firm in their conviction that [J.S. Irvine] wrote the tune, and their belief is corroborated by a member of the family. . . . Miss Irvine, now that the tune has won such widespread favour and honour, deserves her meed of credit, for there is no doubt that she was at least joint-composer.”[9] On Patrick’s expert authority, Irvine’s name started to appear in connection with the tune, including new printings of the Scottish Psalter 1929.

Fig. 9. The Scottish Psalter 1929 (Oxford: University Press, n.d.).

Nevertheless, Irvine’s authorship has been discounted or dismissed by others. In 1958, Fenton Wyness, a historian in Aberdeen, having noticed the change of attribution in a new printing of the Scottish Psalter 1929, published a 24-page booklet, Crimond: The Full Story of a Psalm Tune Controversy, ardently refuting her involvement. Ronald Johnson summarized Wyness’s argument thusly:

Wyness deals with Anna Irvine’s letter by declaring that George Riddell of Rosehearty (1853–1942), who had been associated with Carnie in the preparation of The Northern Psalter, and William Clubb (1835–1915), who had been precentor at Crimond when the tune was written, had assured Mr. Monteith in 1911 that she had made a mistake. There was indeed, they said, a tune composed by Jessie Irvine and harmonized by Grant, but it was called BALLANTYNE and Clubb possessed the manuscript (It does not seem ever to have been published). He and Riddell considered that Anna Irvine had confused the two tunes.[10]

According to Wyness, George Riddell personally contacted R.S. Kemp and R.T. Monteith and vouched for Grant’s authorship, and the key to this was William Clubb, who had known both Irvine and Grant personally. From a written statement by Riddell:

I was privileged to enjoy the friendship of the late Mr. Clubb, long precentor of Crimond Church . . . No one was in a better position to be fully acquainted with the matter than Mr. Clubb, and he discussed the matter in all its bearings. He knew also, beyond the shadow of doubt, that both the melody and harmony of the tune CRIMOND were the work of David Grant.[11]

Hymnologist Erik Routley reviewed the booklet in 1959 and offered these observations and recommendations:

Mr. Wyness does not mince matters. He is quite clear that Anna Barbara was wrong. And it must be admitted that extraordinary mistakes of this kind can occur. . . . And yet it is surely easier to believe what Dr. Patrick wrote. . . . It is almost certainly true that Grant had a good deal to do with the tune. Mr. Wyness makes out a perfectly good case for saying either “David Grant, adapted from a melody by Jessie S. Irvine,” or “Jessie S. Irvine, harmonized and adapted by David Grant.” On the whole, that seems to be the most exact ascription, and perhaps future editors ought to follow it.[12]

Ronald Johnson, writing in 1988, was dismissive of Irvine’s involvement, and risking the ire of Irvine’s supporters in Crimond, stated:

I think that anyone reading Fenton Wyness with care will be convinced by his arguments. . . . The negative case against Jessie Irvine is as solid as the positive one for David Grant. God rest both their souls. I shall not be able to show my face in Crimond again.[13]

The truth undoubtedly lies somewhere in the middle of this, and hymnal editors would not be faulted for using any of the above attributions.

Association of CRIMOND with Psalm 23

Fig. 10. “Crimond,” HMV C-3639 (Nov. 1947).

The combination of CRIMOND and “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want” seems to have entered the public consciousness via performances in this manner by the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, conducted and arranged by Hugh S. Roberton (1874–1952). According to Roberton’s son Kenneth, his father had heard it sung this way by John McEwan, a member of the choir who was also choirmaster of Langside-Shawlands United Free Church in Glasgow, and the Orpheus choir first performed the elder Roberton’s arrangement on 4 April 1936 in the Queen’s Hall, London.[14] Hugh Roberton’s arrangement was published around the same time, “Crimond. Scottish psalm tune (by D. Grant). Arranged for men’s voices with faux-bourdon” (London: Bayley & Ferguson, n.d.). The choir recorded it on 12-inch 78-rpm discs (HMV C-3639) in November 1947, later reissued on 7-inch 45-rpm discs (HMV 7P-247).

The connection was further cemented when Lady Margaret Egerton recommended it for the wedding of Princess Elizabeth Windsor and Prince Philip Mountbatten (20 November 1947), specifically offering the tune and the descant by W. Baird Ross to William McKie, organist of Westminster Abbey, who created an arrangement for the event. McKie’s harmonization was included in the British Methodist Hymns & Psalms (1983). This musical offering was repeated at a Silver Wedding Anniversary service for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, 26 April 1948.

The first appearance of this pairing in a hymnal was in the School Hymn Book of the Methodist Church (1950), followed quickly by the BBC Hymn Book (1951) and Congregational Praise (1951).

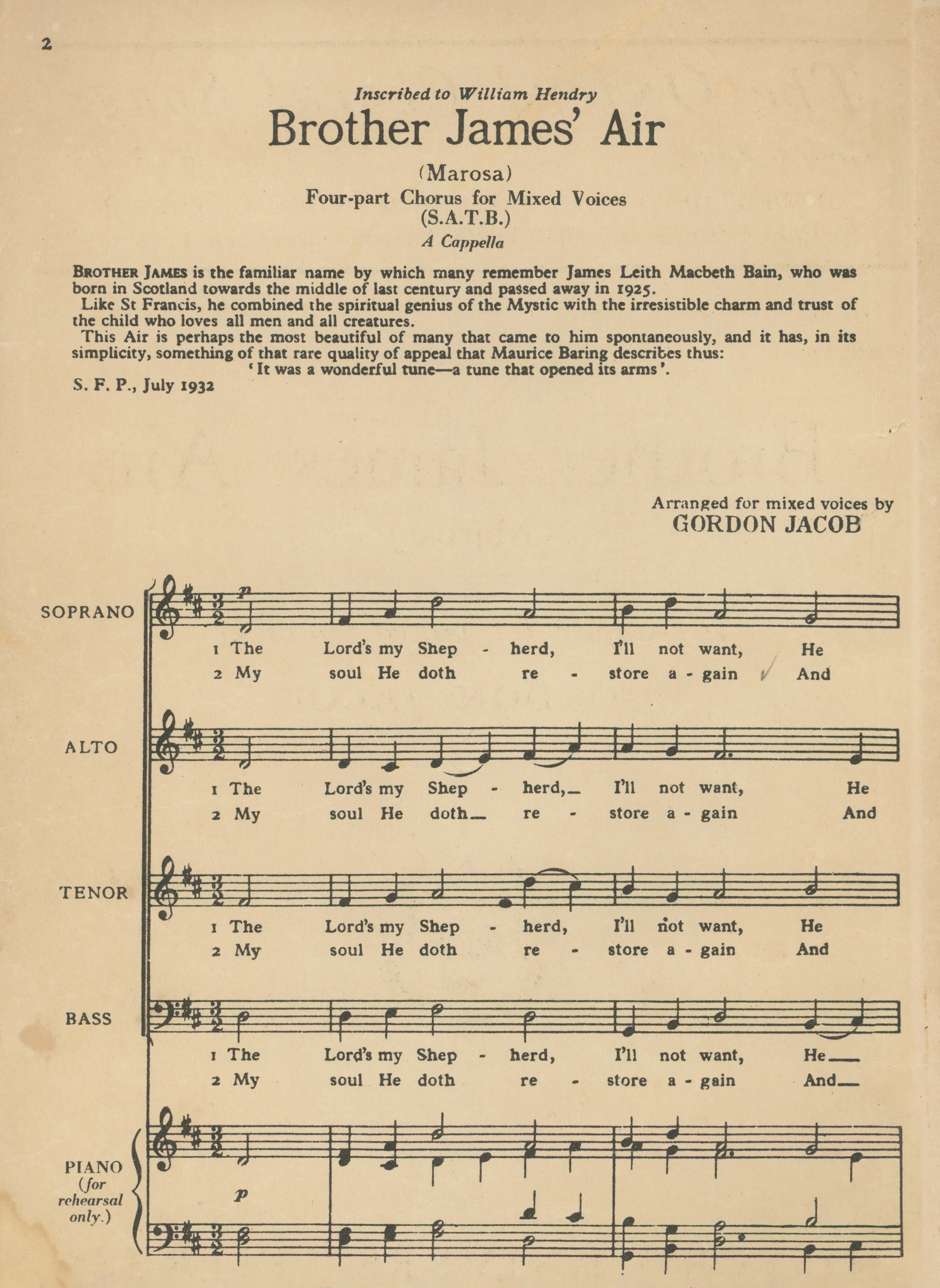

2. BROTHER JAMES’ AIR (MAROSA)

This tune was composed by Scotsman James Leith Macbeth Bain (1860–1925), who has been described as a “healer, mystic, and poet,”[15] and founder of the Brotherhood of Healers. It was first published in Bain’s collection The Great Peace (1915 | Fig. 11), which was printed in four successive editions in 1915, the fourth of which is dated March 1915. The tune does not appear in the first edition; it is present in the fourth (we have not yet examined the second and third eds.). Bain called the tune MAROSA after the seventh daughter of his friend Captain M’Laren and dedicated it to William Hendry. He paired it with the Scottish Psalm 23 (“the old, classic Shepherd-Psalm”), except as he explained in his prefatory note, he added several repetitions of certain segments of the text in order to suit his tune. At the time, World War I was raging in Europe (1914–1918); Bain felt this hymn was “a potent requiem for the blessing of those dear men who have fallen in this war.”

Fig. 11. The Great Peace, 4th ed. (London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1915).

This tune was popularized via an arrangement by Gordon Jacob (1895–1984), teacher of composition at the Royal College of Music for forty years (1926–1966). Jacob called it “Brother James’ Air” and initially set it for unison voices with piano accompaniment in 1932 (Fig. 12), then later offered other versions for mixed voices (1934), female voices (1935), and even a recorder trio (1963). Jacob’s SATB harmonization from 1934 is sometimes included in hymnals by way of an simplification made by Walter M. Gelton for A Hymnal for Friends, 2nd ed. (1955).

Fig. 12a. Gordon Jacob, “Brother James’ Air” (Oxford: University Press, 1932), excerpt.

Fig. 12b. Gordon Jacob, “Brother James’ Air” (Oxford: University Press, 1934), excerpt.

Fig. 12c. A Hymnal for Friends (Philadelphia: Friends General Conference, 1955), excerpt.

3. BELMONT

One other tune closely associated with the Scottish paraphrase of Psalm 23 is BELMONT, which is believed to be based on a tune by William Gardiner (1770–1853) from Sacred Melodies, vol. 1 (1812 | Fig. 13). In the original printing, the melody was structured as Long Meter Double and set to the text “Come hither, all ye weary souls” by Isaac Watts. Although the composer was not credited here, Gardiner claimed it as his own in a catalog appended to his book Music and Friends (1838).

Fig. 13. Sacred Melodies, vol. 1 (1812).

The version of the tune as it is generally used today, rendered in Common Meter, is from a collection made by Charles Severn, Psalm & Hymn Tunes, Chants, &c., for the Use of the Parish Church of St. Mary, Islington (Islington: Charles Severn, 1853 | Fig. 14), where Severn assigned the name BELMONT for unknown reasons and did not credit an author. Given the resemblance of the first four measures of Gardiner’s tune to the general shape of Severn’s, scholars generally credit the latter as being derived from the former.

Fig. 14. Psalm & Hymn Tunes, Chants, &c., for the Use of the Parish Church of St. Mary, Islington (Islington: Charles Severn, 1853).

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

10 May 2021

rev. 28 May 2021

Footnotes:

The Booke of Psalmes in English Meeter (Rotterdam: Henry Tutill, 1638), preface.

Beth Quitslund, The Reformation in Rhyme (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 293–297.

Henry Alexander Glass, The Story of the Psalters (1888), pp. 36–37: Archive.org

Thomas Young, The Metrical Psalms and Paraphrases: A Short Sketch of Their History (1909), p. 77: Archive.org

Thomas Young, The Metrical Psalms and Paraphrases: A Short Sketch of Their History (1909), p. 63: Archive.org

William Carnie, Additional Aberdeen Reminiscences, vol. 3 (Aberdeen University Press, 1906), p. 230: HathiTrust

Quoted in Ronald Johnson, “How far is it to Crimond?” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3 (July 1988), p. 40.

Quoted in Ronald Johnson, “How far is it to Crimond?” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3 (July 1988), p. 40.

Millar Patrick, “Psalm Twenty-Three and the Tune ‘Crimond,’” HSGBI Bulletin, no. 44 (1948), p. 8; no. 46 (1949), p. 80.

Ronald Johnson, “How far is it to Crimond?” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3 (July 1988), p. 41.

Fenton Wyness, Crimond: The Full Story of a Psalm Tune Controversy (1958), p. 15.

Erik Routley, “Crimond Again,” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 4, no. 13 (Summer 1959), pp. 195–196.

Ronald Johnson, “How far is it to Crimond?” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3 (July 1988), p. 42.

Ronald Johnson, “How far is it to Crimond?” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3 (July 1988), p. 38.

Bert Polman, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Psalter Hymnal Handbook (Grand Rapids: CRC, 1998), p. 300.

Related Resources:

Francis Rous, The Booke of Psalmes in English Meeter

(1638): PDF

(1641): PDF

(1643): PDF

(1646): PDF [Westminster Revision]

Zachary Boyd, The Psalmes of David in Meeter

(1646): PDF (2nd ed.)

(1646): PDF (3rd ed.)

(1648): PDF

Kirk of Scotland, The Psalms of David in Meeter (1650): PDF

William Carnie, The Northern Psalter and Hymn Tune Book, Addenda Ed. (Abderdeen: Lewis Smith, Taylor & Henderson, 1877): Archive.org

James Mearns, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” A Dictionary of Hymnology, ed. John Julian (London: J. Murray, 1892), p. 1154: HathiTrust

William Tough, ed., The Works of Sir William Mure of Rowallan, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1898), p. 53 etc.: Archive.org

James Moffatt & Millar Patrick, “CRIMOND,” “David Grant,” Handbook to the Church Hymnary with Supplement (Oxford: University Press, 1935), pp. 70–71, 109.

Millar Patrick, “Psalm Twenty-Three and the Tune ‘Crimond,’” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 3 (July 1948), pp. 8–9; vol. 2, no. 6 (April 1949), p. 80.

Millar Patrick, Four Centuries of Scottish Psalmody (Oxford: University Press, 1949).

Erik Routley, “CRIMOND,” Companion to Congregational Praise (London: Independent Press, 1953), p. 306.

Fenton Wyness, Crimond: The Full Story of a Psalm Tune Controversy (Aberdeen: W. & W. Lindsay, 1958): WorldCat

Erik Routley, “Crimond Again,” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 4, no. 13 (Summer 1959), pp. 195–196.

Ronald Johnson, “How far is it to Crimond?” HSGBI Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3 (July 1988), pp. 38–42.

Richard Watson & Kenneth Trickett, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Companion to Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing, 1988), pp. 74–75.

Fred L. Precht, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Lutheran Worship Hymnal Companion (St. Louis: Concordia, 1992), p. 429.

Jeffrey Wasson & Robin A. Leaver, “CRIMOND,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3B (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), pp. 1216–1219.

Jeffrey Wasson, “BROTHER JAMES’ AIR,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3B (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), p. 969.

Bert Polman, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Psalter Hymnal Handbook (Grand Rapids: CRC, 1998), pp. 300–301.

Bernard Massey, “Brother James and his air,” HSGBI Bulletin, no. 228 (2001), pp. 174-176.

J.R. Watson, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” An Annotated Anthology of Hymns (Oxford: University Press, 2002), pp. 91–92.

Colin Burrow, “Francis Rous,” Oxford Dictionary of Biography (23 September 2004): DOI

Edward Darling & Donald Davison, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Companion to Church Hymnal (Dublin: Columba, 2005), pp. 69–70.

Carl P. Daw Jr., “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), pp. 759–761.

Christopher I. Thoma & Joe Herl, “The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), pp. 976–978.

University of Aberdeen, Special Collections: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/special-collections/

“Scottish Psalter,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology: http://www.hymnology.co.uk/s/scottish-psalter

“The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want,” Hymnary.org: https://hymnary.org/text/the_lords_my_shepherd_ill_not_want_rous