Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme

translated as

Wake, awake, for night is flying

Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling

Sleepers, wake! a voice astounds us

I. Origins

Lutheran pastor Philipp Nicolai (1556–1608) had accepted a position in the town of Unna, Westphalia, Germany, in 1596, and only a year later, the town was struck by a devastating wave of bubonic plague (“black death”). From July 1597 to January 1598, more than half of the town’s 2,400 residents died. Lutheran scholar Paul Rorem summarized the scenario as follows:

His ministerial records report 300 burials in July 1597 alone, with 170 deaths in one August week that year. The numbers are staggering and must have meant group funerals, which multiplied the grief and fear. His church and residence overlooked the cemetery and its endless mourning. Death seemed in charge, but Pastor Nicolai was steeped in a scriptural hope for new life, as expressed in his major work of spiritual consolation and expectation, the 1599 Mirror of the Joy of Eternal Life.[1]

In a letter to his brother Jeremias, 15 January 1598, Nicolai indicated he had completed the first draft of his devotional tome.[2] The resultant work, Frewden Spiegel deß ewigen Lebens (Frankfurt am Main: Johann Spieß, 1599) has a preface dated 10 August 1598. Part of the preface reads:

There seemed to me nothing more sweet, delightful, and agreeable, than the contemplation of the noble, sublime doctrine of Eternal Life obtained through the Blood of Christ. This I allowed to dwell in my heart day and night, and searched the Scriptures as to what they revealed on this matter; read also the sweet treatise of the ancient doctor Saint Augustine [De Civitate Dei]. . . . Then day by day I wrote out my meditations, found myself, thank God! wonderfully well, comforted in heart, joyful in spirit, and truly content; gave to my manuscript the name and title of a Mirror of Joy, and took this so composed Frewden-Spiegel to leave behind me (if God should call me from this world) as the token of my peaceful, joyful, Christian departure, or (if God should spare me in health) to comfort other sufferers whom He should also visit with the pestilence. . . . Now has the gracious, holy God most mercifully preserved me amid the dying from the dreadful pestilence, and wonderfully spared me beyond all my thoughts and hopes, so that with the Prophet David I can say to Him, “O how great is Thy goodness, which Thou hast laid up for them that fear Thee” [Ps. 31:19] etc.[3]

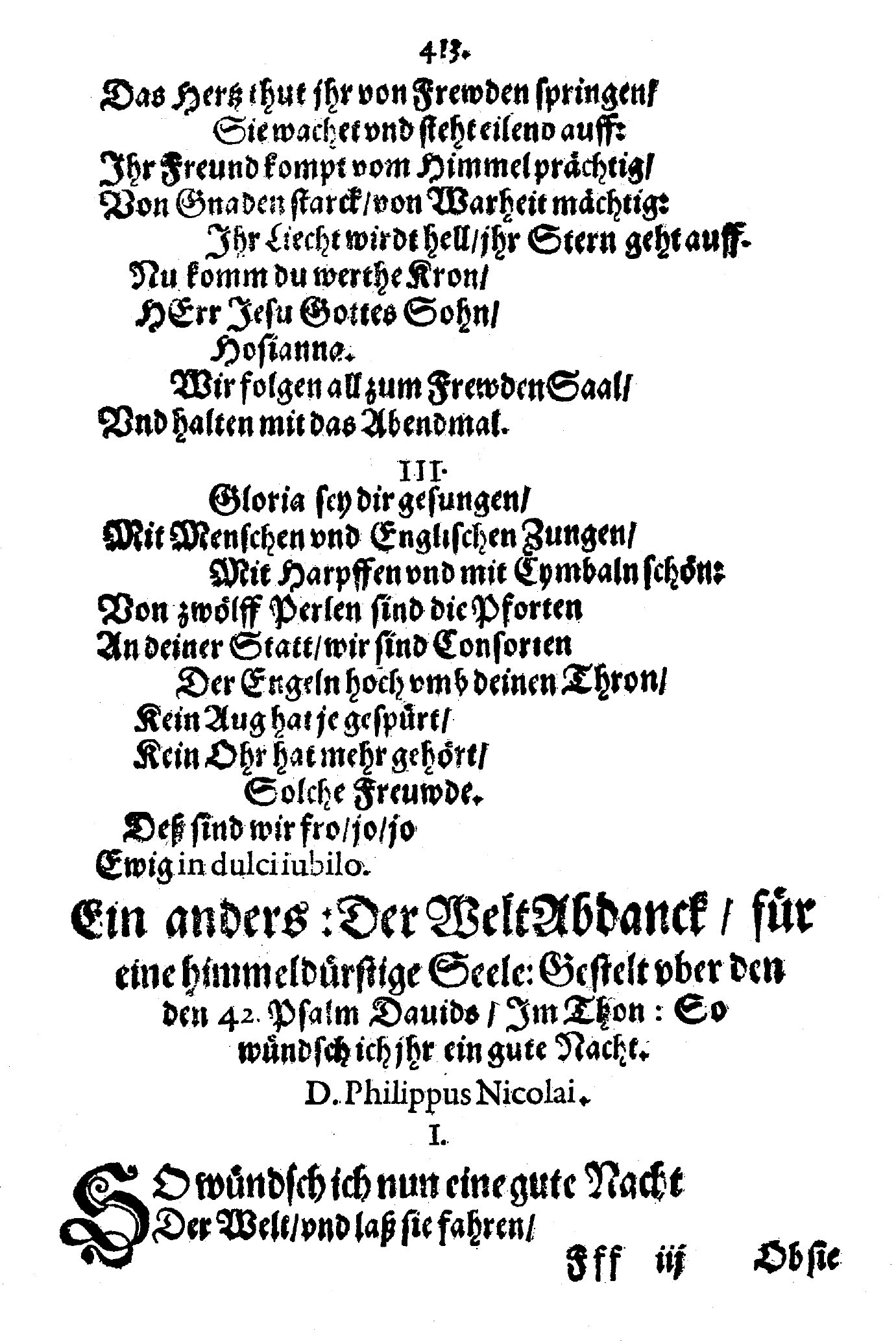

The book includes four hymns—three by Philipp and one by Jeremias. Two of them have been widely adopted into English: this one, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme,” and “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” (“O Morning Star! how fair and bright”).

Fig. 1. Frewden Spiegel deß ewigen Lebens (Frankfurt am Main: Johann Spieß, 1599).

II. Textual Analysis

The original version of “Wachet auf” was headed “Ein anders von der Stim[m] zu Mittemacht, vnd von den klugen Jungfrauwen, die jhrem himmlischen Bräutigam begegnen, Matth. 25” (“Another [hymn] of the voice at midnight and of the wise virgins who go to meet their heavenly bridegroom, Matthew 25”). The text is structured in three stanzas of eleven lines, 898.898.66.4.88 (aabccbddeff).

The first letter of each stanza spells W–Z–G, generally regarded as a backward homage to Graf zu Waldeck, that is, his former student, Count Wilhelm Ernst, who died 16 Sept. 1598 at age 15. A similar acrostic device can be seen in his hymn “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern.”

Nicolai mentioned the parable of the wise and foolish virgins from Matthew 25:1–13 in the devotional portion of his book:

In another place [in Scripture], this life of paradise is called a wedding to which Christ, with His chosen children of the light (who have died a blessed death in the Lord), looks forward; and to this place He will also call back from this vale of tears all who await His coming with believing hearts, as though with burning lamps (Matthew 25). For He compares Himself to a bridegroom who knocks at midnight and whom His devout Christians, like wise virgins, come to meet with burning lamps, going with Him into the wedding; and He exhorts us to constant readiness and expectation of His arrival, saying “Be like those who wait for their lord to set out from the wedding, so that when he comes and knocks they open the door for him at once. Blessed are the servants whom the lord, when he comes, finds awake. Truly I say to you, he will prepare himself for service, and will seat them at the table, and will go before them and serve them” (Luke 12).[4]

James Mearns and others have mentioned allusions to Rev. 19:6–9 (The marriage supper of the Lamb), Rev. 21:21 (gates of pearl, streets of gold), 1 Corinthians 2:9 (“no eye has seen, nor ear heard,” etc.), Ezekiel 3:17 (watchman for the house of Israel), and Isaiah 52:8 (watchmen looking for the return of the Lord).

Mearns felt Nicolai’s text was reminiscent of Wächter-Lieder of the middle ages, “But while in the Songs the voice of the Watchman from his turret summons the workers of darkness to flee from discovery, with Nicolai it is a summons to the children of light to awaken to their promised reward and full felicity.”[5] Likewise, Bach scholar Gerhard Herz noted the earlier tradition:

The poem “Wachet auf . . .” recalls the Minnesinger time of Wolfram von Eschenbach, particularly the Morning Song (Tageweise), in which the watchman on the battlement of the knight’s castle breaks the quiet of the night with his horn call, warning lovers that dawn approaches and they must part. These morning songs were still printed as broadsheets in the 16th century, the century that saw their transformation into sacred watchmen’s songs. The last of them is Nicolai’s magnificent hymn, which has been called the “King of Chorales.” The warning call to the lovers became the watchman’s call to Zion.[6]

Lutheran scholar Joseph Herl likens the second stanza to a phenomenon seen in The Fellowship of the Ring:

In the second stanza, the new Zion hears the watchmen singing. How odd! Watchmen do not sing; they shout. But the news is so joyous that they cannot help themselves, just as Frodo Baggins and his hobbit companions, safe in the house of Tom Bombadil after a dangerous journey, began to sing merrily instead of talking. And the Bride is no longer just a solitary individual, but the whole of the new Zion, the Church.[7]

Regarding the third stanza, Herl offers:

The third stanza gives us what Jesus’ parable omitted; namely, the end of the story. Here we find out what happens after the wedding party enters the hall, and surprisingly, it is not the banquet that is the focus, but . . . it is the music. . . . At the end of the original hymn, the German language simply is not powerful enough to express the singer's joy, so the singer lapses at first into stuttering: “Deß sind wir froh, io, io” (loosely, “Therefore we have joy, oy, oy”). Then a completely new, ecstatic, language breaks forth, not German, but Latin: “Ewig in dulci jubilo” (“eternally in sweetest jubilation”), a reference to the macaronic (Latin and German) hymn “In dulci jubilo, nun singet und seid froh.”[8]

III. Tune

Nicolai’s tune was written in a time when music was largely structured by phrases rather than by barlines. The note values are constrained to wholes and halves, and the melody, written in C clef, spans a diatonic octave from F below to F above middle C. Some of the melodic leaps, including the opening triad, evoke the harmonics of a brass instrument, like a fanfare. Like many church tunes of the time, the melody is in rounded bar form, or AAB, with the last phrase of B duplicating the last phrase of A.

Some commentators have observed traits in common with older tunes. One potential antecedent influence is a tune by Hans Sachs (1494–1576), “Silberweise,” composed in Braunau in 1513, shown below as in Der Meistergesang in Geschichte und Kunst (Leipzig: Hermann Seemann Nachfolger, 1901), edited by Curt Mey. Mey included two versions, using manuscripts from Zwickau and Jena. In either case, the only resemblance is in Sachs’ third phrase in comparison to Nicolai’s final phrases in the A (Aufgesang) and B (Abgesang) sections. The Zwickau version (the version most widely cited) has a similar phrase in the Abgesang. It’s a common formula, which Mey actually likens to the final phrase of Martin Luther’s “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” rather than to Nicolai’s tune.

Fig. 2. Der Meistergesang in Geschichte und Kunst (Leipzig: Hermann Seemann Nachfolger, 1901).

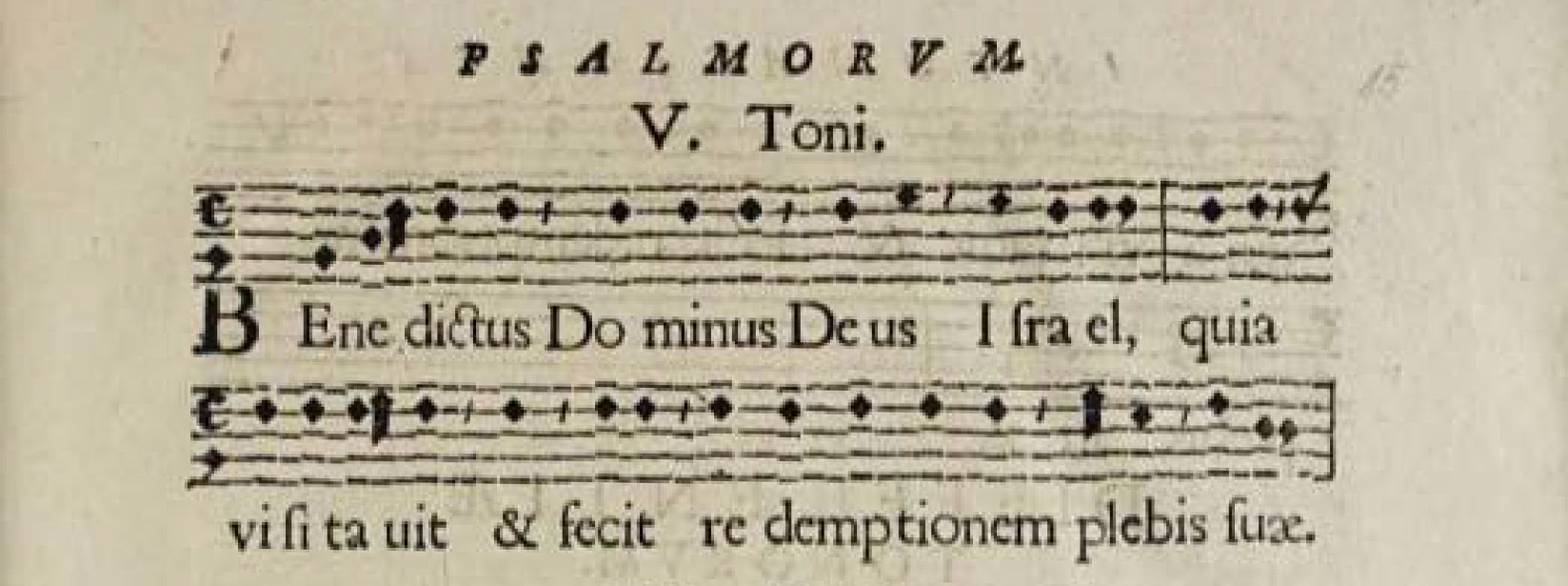

Some commentaries point to the similarity between WACHET AUF and the fifth Gregorian psalm tone (a reciting tone), which can be seen here in an example from Vesperale et Matvtinale (1589), compiled by Matthaeus Ludecus for Havelberg Cathedral. This formula begins with an upward triad and ends by resolving from 5 to 3. Rising triads are common in music, so the possible connection between the two tunes is impossible to know for sure.

Fig. 3. Vesperale et Matvtinale (1589).

Another possible influence is the opening line of “In dulci jubilo,” a carol Nicolai quoted in his stanza 3.

Given the limited similarities to Sachs and the fifth psalm tone, what we find here is Nicolai simply using the melodic building blocks of the time, using them to craft his own melody. As Carl Daw put it, “Such borrowings and resemblances reflect the tune’s participation in the developing stream of congregational song.”[9] Similarly, Gerhard Herz offered:

Like Luther’s “Christ lag in Todesbanden,” so too is Nicolai’s hymn tune assembled with great ingenuity from older melodic phrases. The sequence of composition recalls Meistersinger procedure: creation of a poem, borrowing of melodic fragments, and welding them into a new melodic whole that fits the poem.[10]

Nicolai’s tune has been known as the “King of Chorales” (his tune for “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” being the “Queen”), a label tracing to Christian David Friedrich Palmer (1811–1875), from an unknown source, but referenced in Eduard Emil Koch’s Geschichte des Kirchenlieds und Kirchengesangs, vol. 2 (1847), pp. 267–268.[11] Methodist scholar Gregory Arthur Stephen said of it, “Great as is Luther’s hymn, this of Nicolai, taking hymn and tune together, is probably the supreme example in hymnody of words and music obeying a single inspiration.”[12] Hymnologist Erik Routley said, “‘Wachet auf’ is a visionary and intensely scriptural song of the Second Coming and the comfort which suffering mortals can take in the thought of it.”[13] Eduard Koch called it “a precious pearl in the hymnodic wreath of the Lutheran Church.”[14]

The hymn can be used for Advent, but it is most often used at the end of the liturgical year, in anticipation of the second coming of Christ.

IV. Harmonizations in Masterworks

Nicolai’s hymn is known to many people through the cantata arrangement of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Cantata BWV 140, including his chorale harmonization, which has appeared in hymnals. This cantata was written for the 27th Sunday after Trinity Sunday, 25 November 1731, performed at the Thomaskirche and/or the Nikolaikirche in Leipzig. A Sunday for Trinity 27 is uncommon, depending on an early Holy Week, so it was not included in his major cantata composing cycles in 1723–24 and 1724–25. Nicolai’s tune appears three times in the seven movements (1, 4, 7). One analyst, W. Murray Young, described the action thusly:

As the watchman calls midnight from his post on the battlements of Jerusalem, we hear the steady step-motif in the tempo which denotes an approaching procession. This rhythm becomes more agitated, as the sleepers wake up and prepare to meet the Bridegroom. Bach’s magnificent word-painting brings this picture to life; we can visualize their consternation and also their joy, which emerges in their florid, emotional “Allelujah!” . . .

The drama of the previous numbers is continued in this second verse of the chorale. The tenor has the role of commentator in this cantata, but his description here of the arrival of the wedding procession in front of the dining-hall is a miniature solo drama in itself. Bach’s setting of this stanza with unison strings has a mystical quality about it, which enhances the tenor’s singing of this verse. Note that “Zion” represents the bride in this number. . . .

The four-part choir and all instruments depict the supreme joy of heaven in this third and last verse of this hymn. The wedding is over and the guests are all rejoicing, in the hope that they too may have such a heavenly marriage. The joyful singing of all the participants at the feast makes this conclusion as dramatic as any of the other parts of this cantata. Their singing of this remarkable verse paints a vision of heaven, depicted both in the text and in the music.[15]

Another key feature of the opening movement is the use of the horn to double the melody in the soprano part, “an instrument the people of Bach’s day would have recognized as akin to the signalling instruments used by town watchmen.”[16]

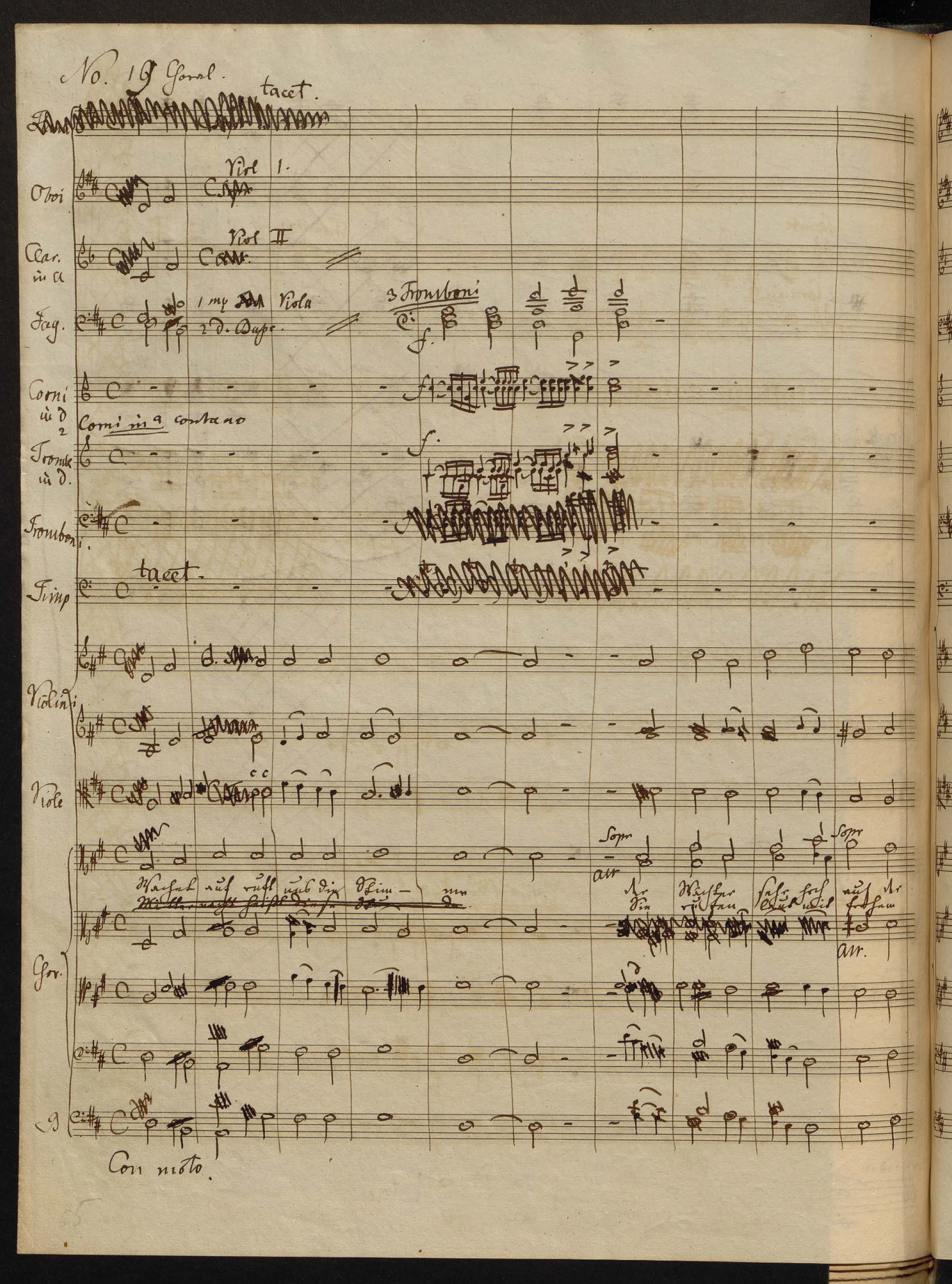

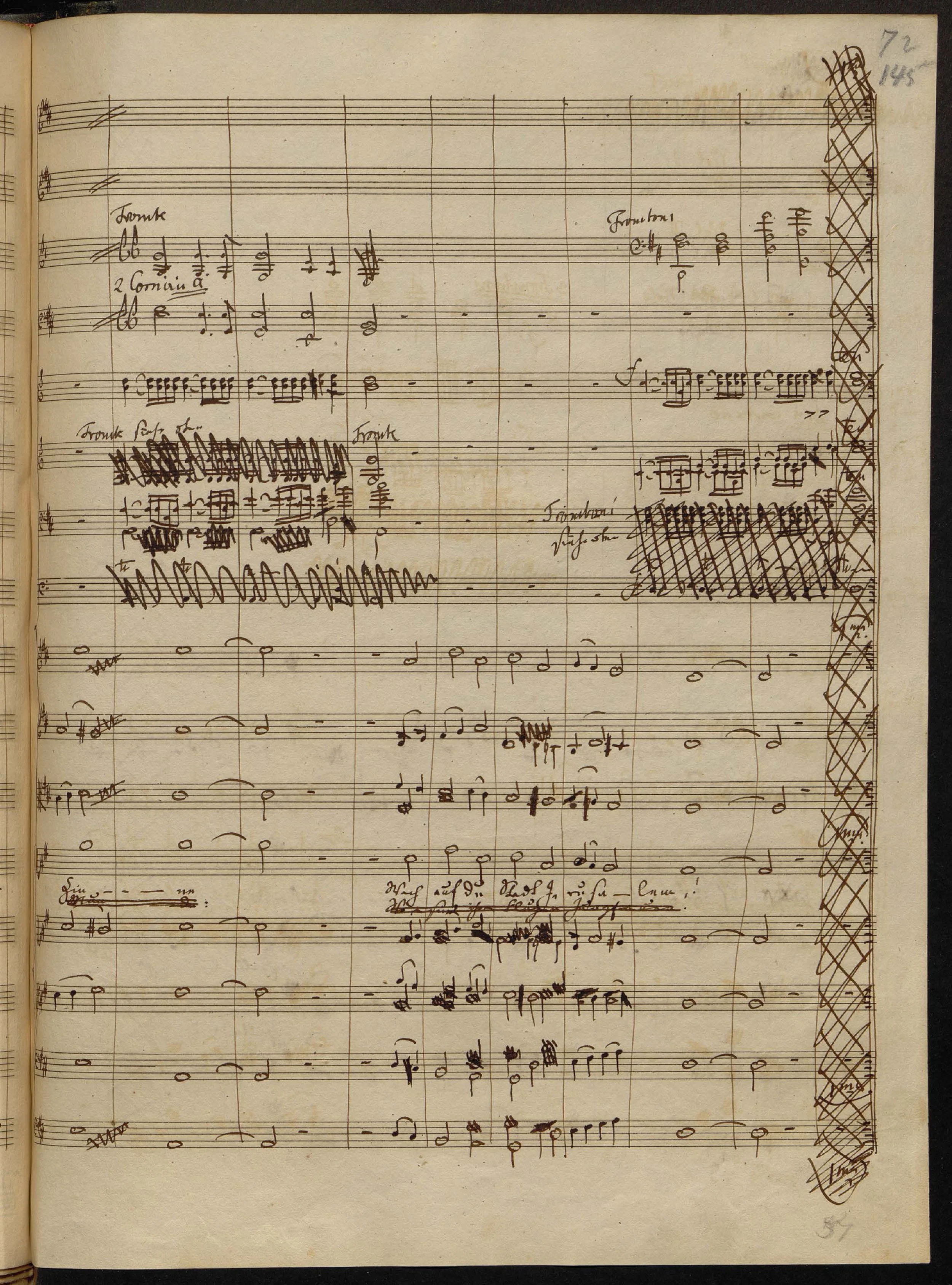

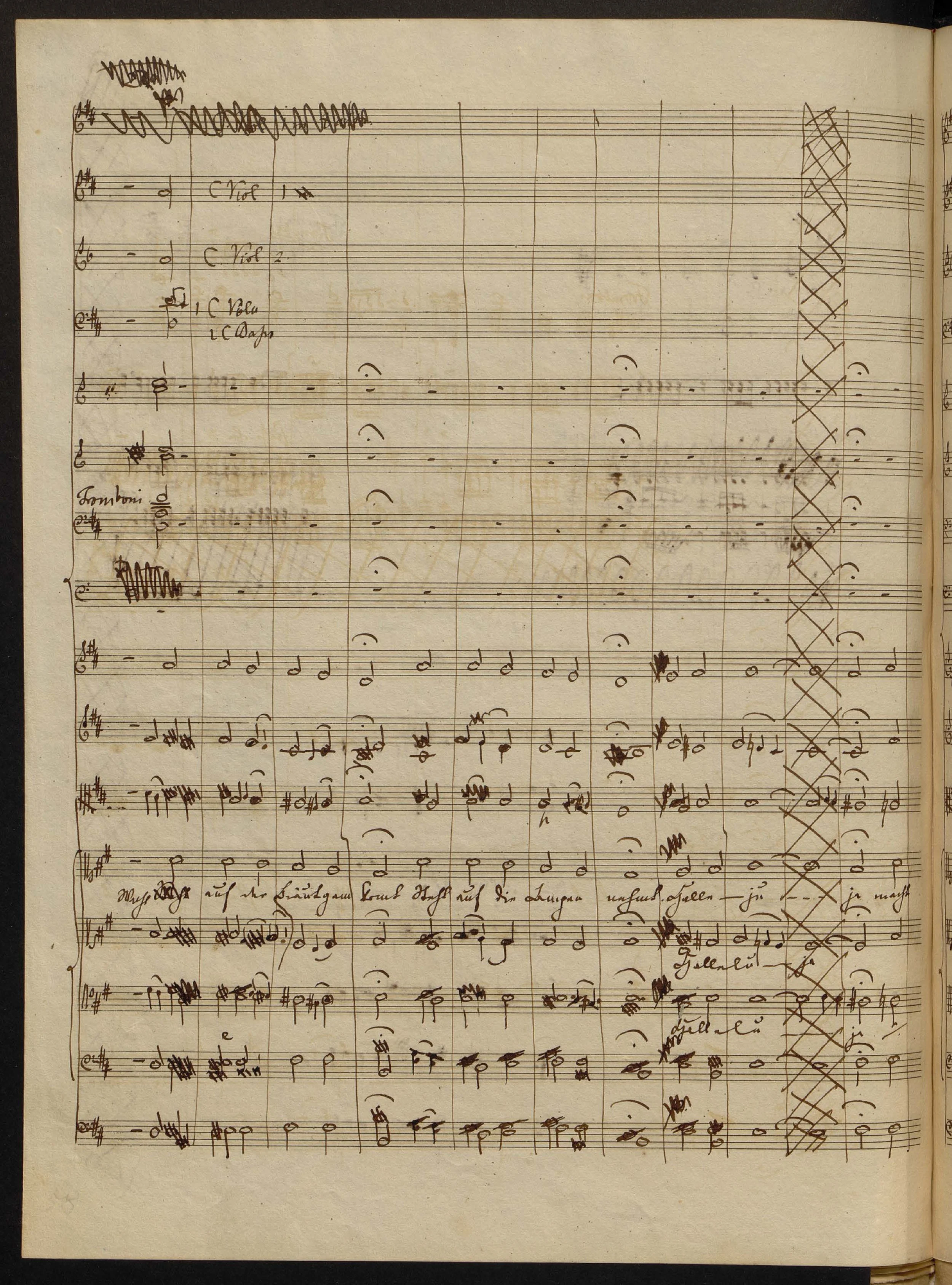

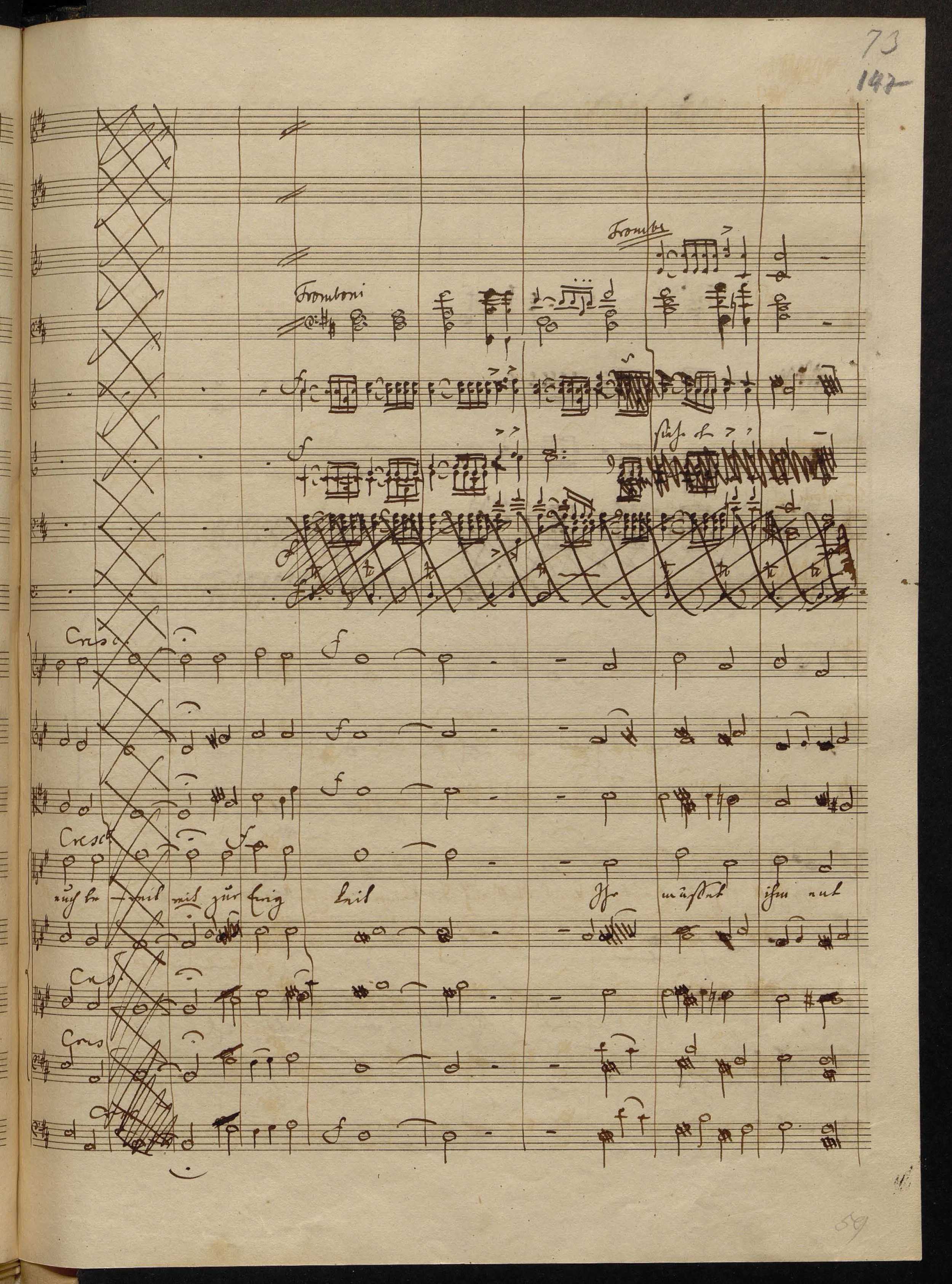

An original manuscript set of the choral and instrumental parts in the hand of Bach and his copyists is held by the Bibliothek der Thomasschule, Leipzig. The horn part includes the elongated version of the melody in the first movement and the chorale version in the last. The first nine staves are in the hand of his pupil Johann Ludwig Krebs (1713–1780), whereas the remainder of the sheet is in Bach’s hand.

The complete chorale harmonization can be seen in a manuscript copy made ca. 1755 by copyist Carl Friedrich Barth (1734–1813).

Fig. 4. Cantata BWV 140, horn part. Bibliothek der Thomasschule, D-LEb Thomana 140 (via Bach-Archiv Leipzig / Bach Digital).

Fig. 5. Cantata BWV 140, condensed score. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 1141 (via Bach Digital).

Aside from rhythmic changes consistent with the musical-cultural shift toward isometric chorale melodies over 130 years, Bach’s version of the melody is most notably different from Nicolai’s in the simplified ending of the first phrase and the descending scale in the second phrase (versus a simple leap in Nicolai). Hymnologist Erik Routley described the changes as being generally for the better, saying, “Bach has straightened out the rhythm, added passing notes, and with his excellent sense of congregational fitness, altered the second line so that the congregation is brought down as soon as possible from the very high note.”[17]

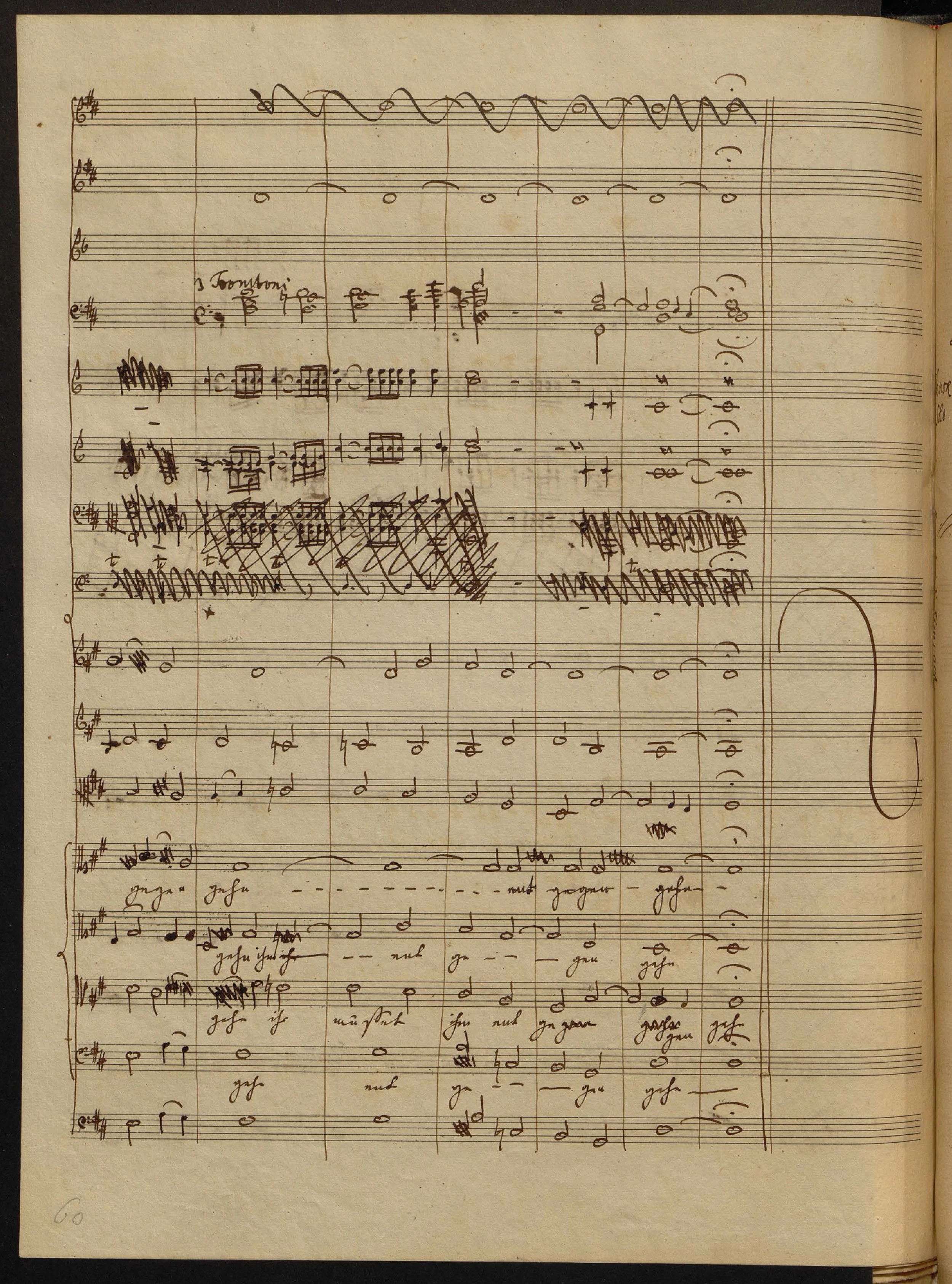

Some hymnals use the harmonization by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847), from his Paulus (St. Paul), which was completed in 1836. Shown here is the orchestral manuscript, as held by Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. The melody aligns well with Nicolai’s original, except in the second phrase, where the end of that phrase is effectively given to the basses. It also omits the repeated A section. Of this version, Erik Routley noted, “Mendelssohn’s arrangement, used in some books and appearing in our old anthem book, is closer to the original and less congregationally approachable.”[18]

Fig. 6. Felix Mendelssohn, Paulus (1836) MS, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (via IMSLP).

The English score, originally published by Novello, includes a prose translation by William Ball, “Sleepers, wake! a voice is calling.”

Fig. 7. Saint Paul (London, Novello, n.d.).

The first known translation of this hymn into English was in Lyra Davidica (1708), an anonymous paraphrase beginning “Awake ye voice is crying / O th’ Watchmen from their towers espying.” This version has not endured, but it represents the tune’s first appearance in an English hymnal.

V. Translation by Winkworth

Catherine Winkworth (1827–1878) produced a translation for Lyra Germanica, Second Series (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1858), beginning “Wake, awake, for night is flying.”

Fig. 8. Lyra Germanica, Second Series (1858).

In her work, Christian Singers of Germany (1869), she expressed Nicolai’s place in the progression of hymnody, especially following the Lutheran Reformation, as follows:

As yet most hymns were addressed to God the Father through our Lord Jesus Christ, or to the Holy Trinity, or in the case of hymns of sorrow and penitence to the Saviour. But afterwards the mystical union of Christ with the soul became a favourite subject; more secular allusions and similes were admitted, and a class of hymns begins to grow up, called in Germany “Hymns of the Love of Jesus.” Some of these are extremely beautiful, and express most vividly that sense of fellowship with Christ, of His presence and tender sympathy, of personal love and gratitude to Him, which are among the deepest and truest experiences of the Christian life; but it is a style which needs to be guarded, for it easily degenerates into sentimentality of a kind very injurious alike to true religion and poetical beauty. The earliest examples of this style are two celebrated hymns written by Dr. Philip Nicolai.[19]

Winkworth’s translation also appeared without change in her Chorale Book for England (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1863) with the original chorale tune. The melody here follows Nicolai’s original shape rather than Bach’s. The harmonization, uncredited, is presumably by one of the book’s music editors, William Sterndale Bennett (1816–1875) or Otto Goldschmidt (1829–1907), but it could be older. According to Rosemary Firman, a scholar of Bennett’s works, “In many cases the original harmonies were retained; where this was not possible, they were provided by Bennett in an appropriate style.”[20]

Fig. 9. Chorale Book for England (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1863).

VI. Translation by Burkitt

The most popular translation in England, “Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling” is by Francis Crawford Burkitt (1864–1935), a professor of divinity at Cambridge University, first published in The English Hymnal (Oxford: University Press, 1906). Like Winkworth, Burkitt’s text is faithful to the German, except in the third stanza he has lost the original “Harfe und mit Zimbeln” (“Harp and with cymbals”), and also omitted the allusion to 1 Corinthians 2:9 (“Eye has not seen, nor ear heard,” etc., NKJV).

Fig. 10. The English Hymnal (Oxford: University Press, 1906).

One of the chief editors of The English Hymnal, Percy Dearmer, was ultimately unsatisfied with Burkitt’s translation and was involved in preparing a revision for Songs of Praise (1925). He later wrote, “Professor Birkett made an admirable version in The English Hymnal, but we were compelled by our advisory committee to attempt yet another, so as to transfer the phraseology more evidently to the present day.”[21] The committee’s revision has not endured.

VII. Translation by Daw

A more recent translation in circulation is by Carl P. Daw Jr. (1944–), made for The Hymnal 1982 (NY: Church Publishing, 1985). In his commentary for The Hymnal 1982 Companion (1994), which implicitly references Mendelssohn’s translation, he wrote:

For the current hymnal, it was thought desirable to have a fresher translation that conveyed more of the narrative and vigor of the German text. . . . It incorporates elements from a number of extant translations, such as the opening two words (which have become the standard way of identifying this text in English), yet manages to approximate some of the immediacy of the original. In particular, it is once again clear that those who read or sing this text are being addressed by a call to watchfulness. To achieve its present form, the text prepared for the report to General Convention in 1982 was slightly altered by the translator in response to suggestions during hearings at the convention. An uncorrected form of this translation has been published in the hymnal Rejoice in the Lord (Grand Rapids, MI, 1985).[22]

In The Hymnal 1982, Daw’s text appeared with two versions of the tune: Bach’s version, and the Nicolai’s original.

Fig. 11. Rejoice in the Lord (1985), excerpt.

Fig. 12. The Hymnal 1982 (1985), excerpt.

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

11 December 2025

Footnotes:

Paul Rorem, Singing Church History: Introducing the Christian Story through Hymn Texts (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2024), p. 119.

Ludwig Curtze, D. Philipp Nicolai’s Leben und Lieder (Halle: J. Fricke, 1859), p. 157: HathiTrust

Translated as in James Mearns, “Philipp Nicolai,” A Dictionary of Hymnology, ed. John Julian (London: J. Murray, 1892), p. 805: HathiTrust

Philipp Nicolai, Frewden Spiegel (1599), p. 311. Translated by Joseph Herl in “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), p. 472.

James Mearns, “Philipp Nicolai,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (1892), p. 806: HathiTrust

Gerhard Herz, Cantata No. 140: The Score of the New Bach Edition (NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 1972), pp. 55–56.

Joseph Herl, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), p. 473.

Joseph Herl, Lutheran Service Book Companion, vol. 1 (2019), p. 473.

Carl P. Daw Jr., “Sleepers, wake! A voice astounds us,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), p. 355.

Gerhard Herz, Cantata No. 140: The Score of the New Bach Edition (NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 1972), p. 56.

For more on this, see Joseph Herl, Lutheran Service Book Companion, vol. 1 (2019), p. 474.

G.A. Stephen, Praises with Understanding (London: Epworth, 1936), p. 211.

Erik Routley, Panorama of Christian Hymnody (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1979), p. 82.

Eduard Koch, Der Lutheraner (St. Louis: LCMS), vol. 14, no. 25, p. 197, translated by Matthew Carver in The Joy of Eternal Life (St. Louis: Concordia, 2021), p. viii.

W. Murray Young, The Cantatas of J.S. Bach: An Analytical Guide (London: McFarland & Co., 1989), pp. 120–121.

Calvin R. Stapert, My Only Comfort: Death, Deliverance, and Discipleship in the Music of Bach (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000), p. 210.

Erik Routley, “Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling,” Companion to Congregational Praise (London: Independent Press, 1953), p. 316.

Erik Routley, Companion to Congregational Praise (1953), p. 316.

Catherine Winkworth, Christian Singers of Germany (London: MacMillan, 1869), pp. 158–159: Archive.org

Rosemary Firman, “William Sterndale Bennett,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology: CDH

Percy Dearmer, “Wake, O wake, for night is flying,” Songs of Praise Discussed (Oxford: University Press, 1933), p. 365.

Carl P. Daw Jr., “Sleepers, wake! A voice astounds us,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3A (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), pp. 117–118.

Related Resources:

Theodore Kübler, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Historical Notes to the Lyra Germanica (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1865), pp. 283–284: Archive.org

James Mearns, “Philipp Nicolai,” A Dictionary of Hymnology, ed. John Julian (London: J. Murray, 1892), pp. 805–807: HathiTrust

Johannes Zahn, Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder (Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1892), no. 8405: Archive.org

J.S. Bach, Cantata BWV 140, manuscript by J.S. Bach and Johann Ludwig Krebs, Bibliothek der Thomasschule, D-LEb Thomana 140 (1713):

https://www.bach-digital.de/receive/BachDigitalSource_source_00003263

J.S. Bach, Cantata BWV 140, manuscript copy by Carl Friedrich Barth, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 1141 (ca. 1755):

https://www.bach-digital.de/receive/BachDigitalSource_source_00002089

Luke Dahn, ed., “BWV 140.7,” Bach Chorales: https://bach-chorales.com/BWV0140_7.htm

Marilyn Kay Stulken, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Hymnal Companion to the Lutheran Service Book (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1982), pp. 131–132.

Richard Watson & Kenneth Trickett, “Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling,” Companion to Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing, 1988), p. 170–171.

Fred L. Precht, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Hymnal Companion to Lutheran Worship (St. Louis: Concordia, 1992), pp. 194–196.

C.T. Aufdemberge, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Christian Worship Handbook (Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing, 1997), pp. 234–235.

Bert Polman, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Psalter Hymnal Handbook (Grand Rapids: CRC, 1998), pp. 788–789.

J.R. Watson, “Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling,” An Annotated Anthology of Hymns (Oxford: University Press, 2002), p. 71–72.

Edward Darling & Donald Davison, “Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling,” Companion to Church Hymnal (Dublin: Columba, 2005), pp. 225–227.

Paul Westermeyer, “Wake, awake, for night is flying,” Companion to Evangelical Lutheran Worship (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 2010), pp. 257–259.

Carl P. Daw, Jr., “Sleepers, wake! A voice astounds us,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), pp. 354–355.

Philipp Nicolai, translated by Matthew Carver, The Joy of Eternal Life (St. Louis: Concordia, 2021): Amazon

J.R. Watson, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology: CDH