Psalm 72

Hail to the Lord’s anointed

with

CULMSTOCK

MISSIONARY HYMN

WEBB

CRÜGER

ZOAN

I. Text: Origins

This paraphrase of Psalm 72 by Moravian minister, editor, and publisher James Montgomery (1771–1854) was reportedly created and first performed for Christmas 1821, probably at Fulneck, West Yorkshire, England.[1] Montgomery mentioned the paraphrase in a letter to his friend George Bennet, 9 January 1822:

I will send you an imitation of the 72nd Psalm, which contains glorious prophecies, in the accomplishment of which the isles afar off—the isles even of the South Sea, unknown when these were uttered—are eternally interested.[2]

In April of 1822, Montgomery spoke at Pitt Street Chapel, where Methodist scholar and preacher Adam Clarke (ca. 1760–1832) served as chairman of the program. This account is partly in the words of Montgomery and partly in the words of James Everett:

“I knew the people would not expect me to talk less than an hour, after having sent for me from such a distance: accordingly, I proceeded through every interruption—commencing with the twilight, settling down into darkness, rising again as the light reappeared, and concluding with the full blaze of the renovated illumination;” and by reciting his own elegant version of the 72nd Psalm, of which the learned chairman solicited a copy.[3]

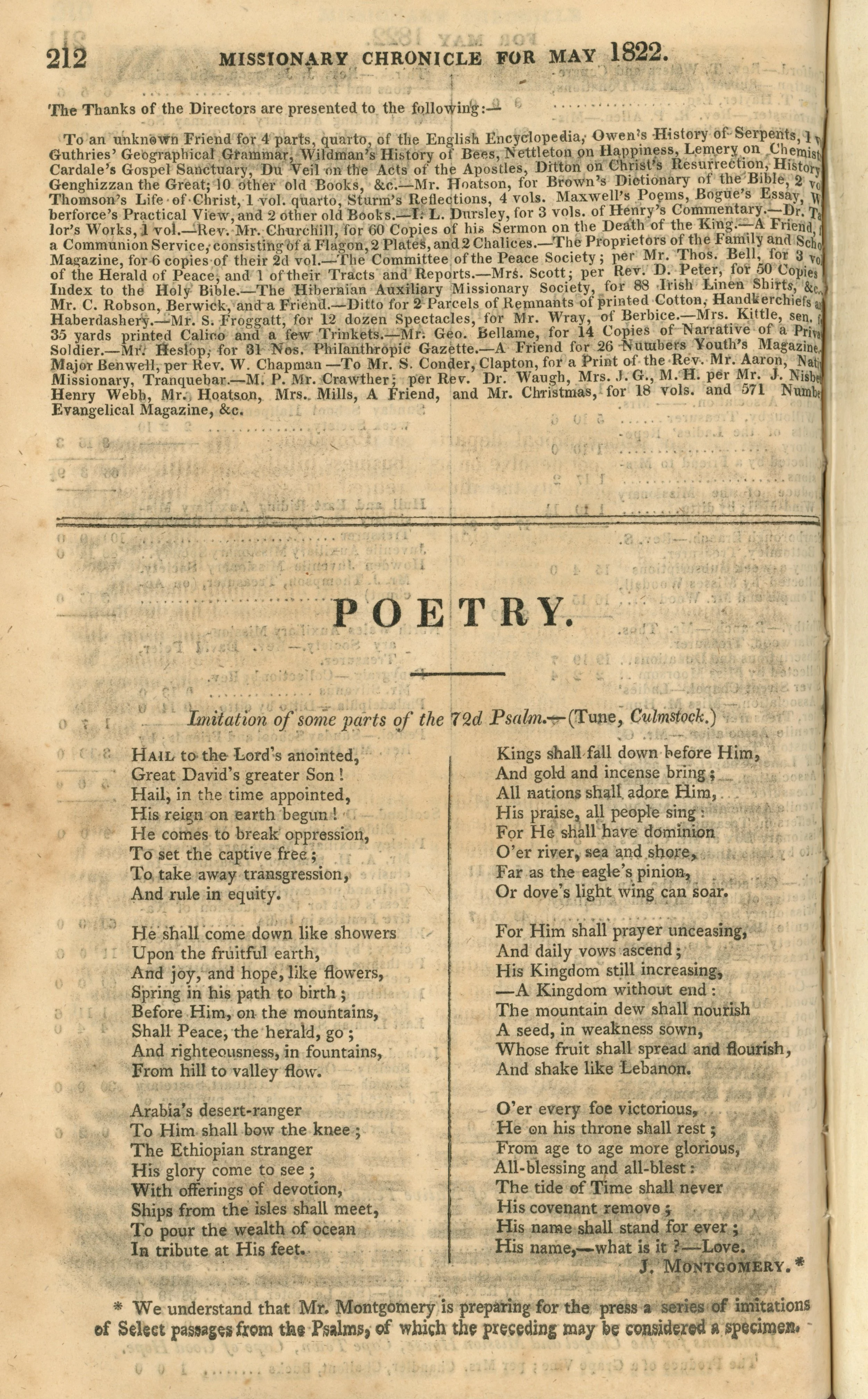

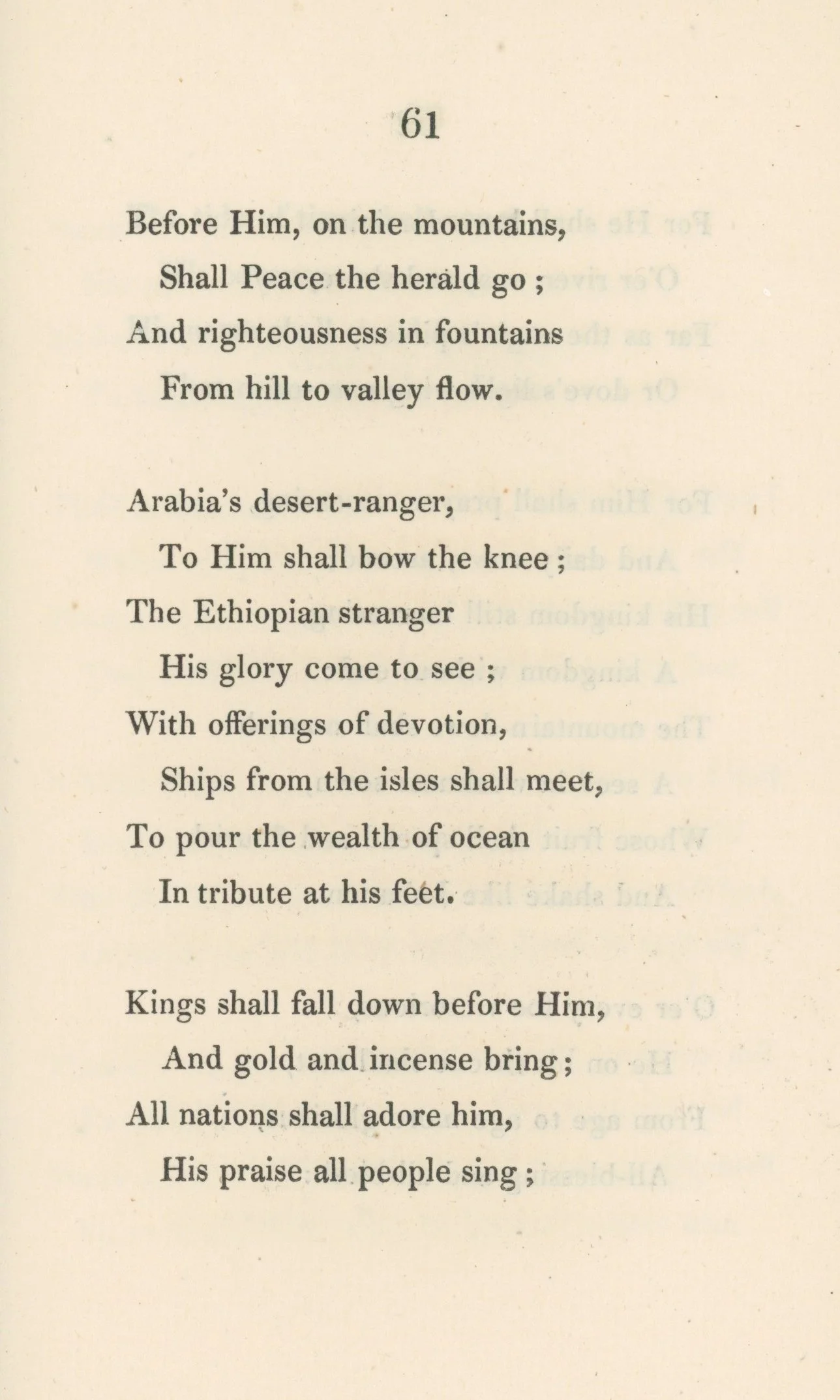

The hymn was first printed in May 1822 in The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, p. 212, in six stanzas of eight lines, where it was headed, “Imitation of some parts of the 72nd Psalm.—(Tune, Culmstock.)” This printing included a notice of Montgomery’s impending publication of Songs of Zion.

Fig. 1. The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle (May 1822).

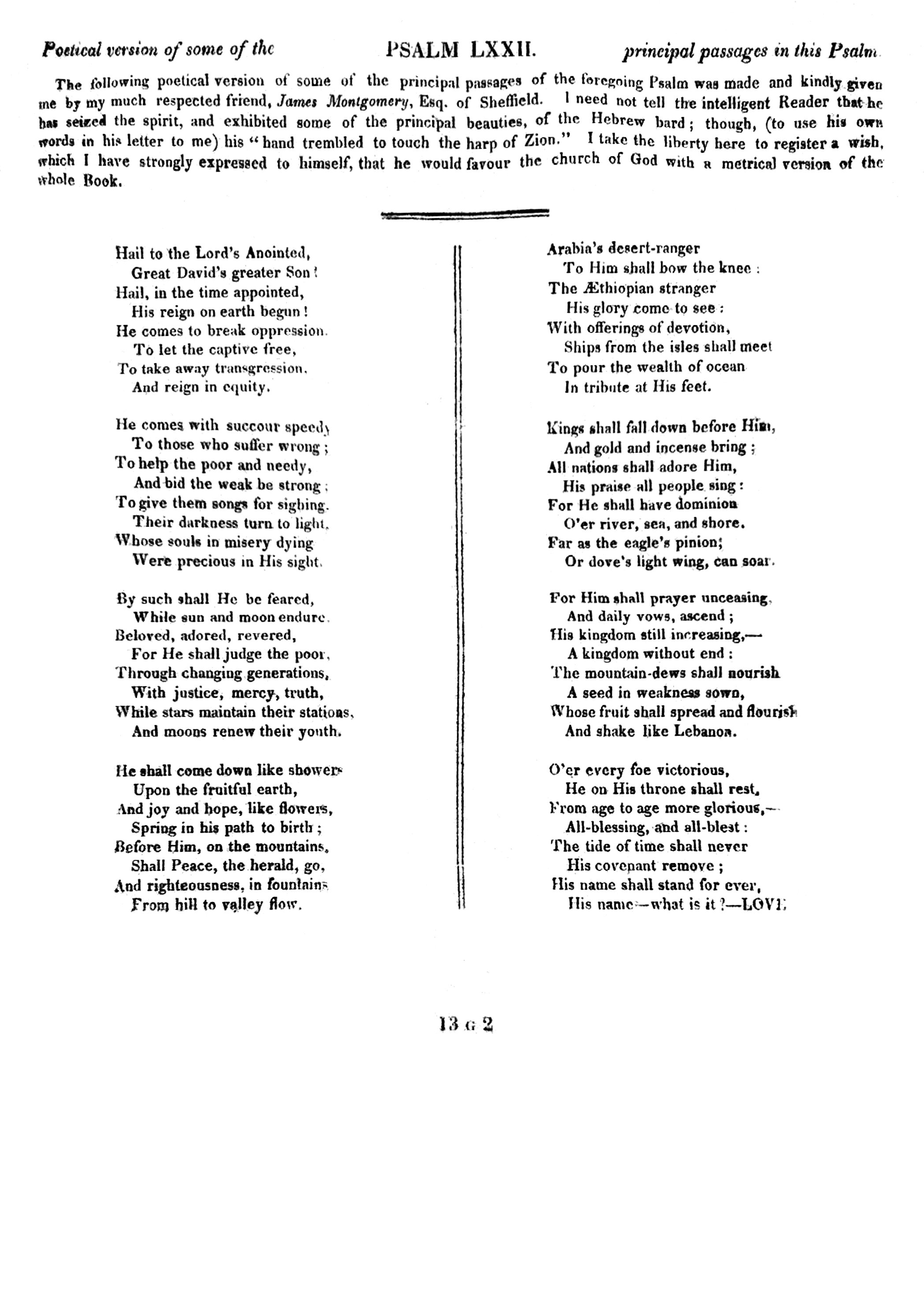

The manuscript Montgomery had given to Adam Clarke in April was put to use through the hymn’s inclusion in Clarke’s Commentaries on the Poetical Parts of the Holy Bible (Philadelphia: J.F. Watson, 1822), naturally placed at the end of Clarke’s commentary on Psalm 72.

Fig. 2. Commentaries on the Poetical Parts of the Holy Bible (Philadelphia: J.F. Watson, 1822).

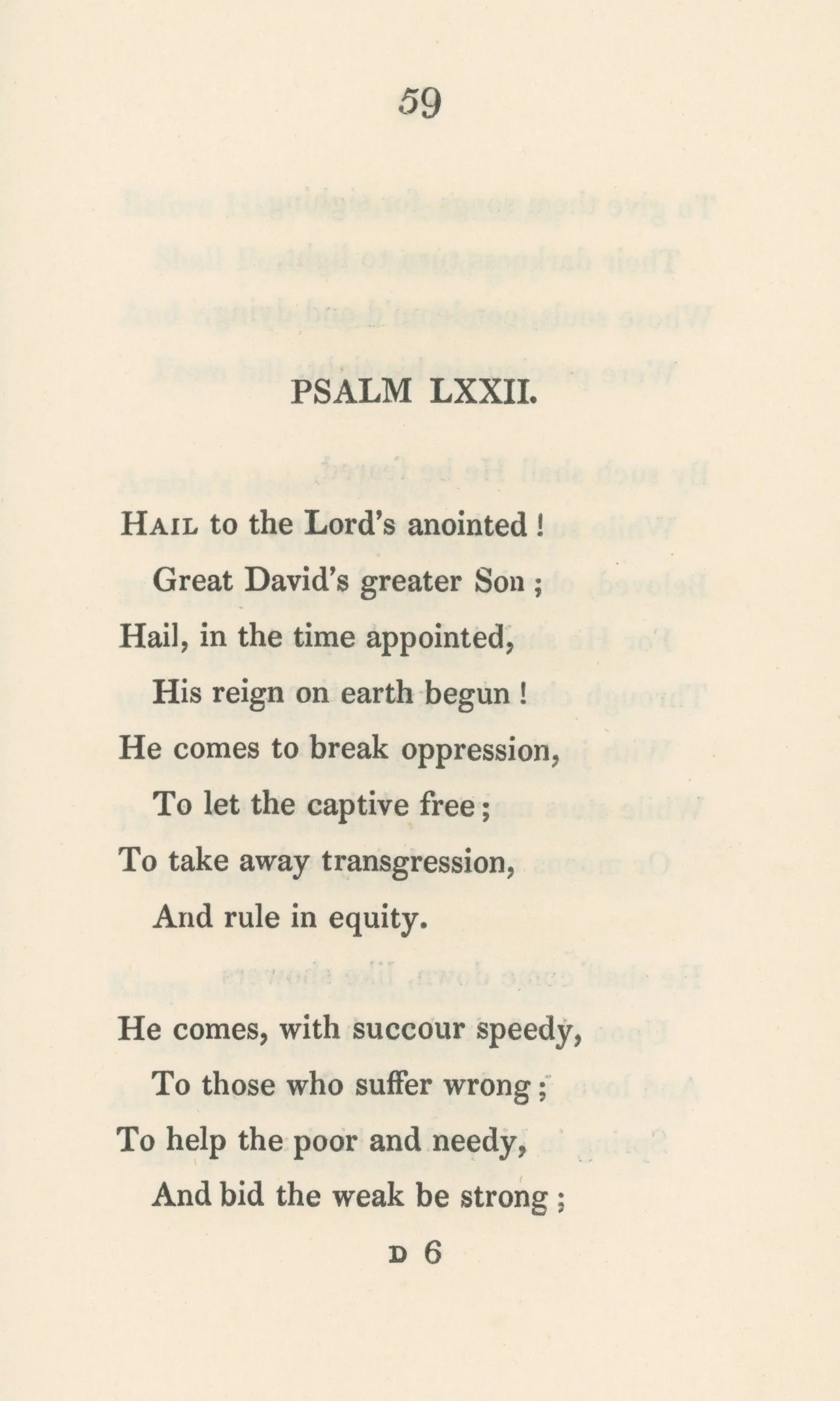

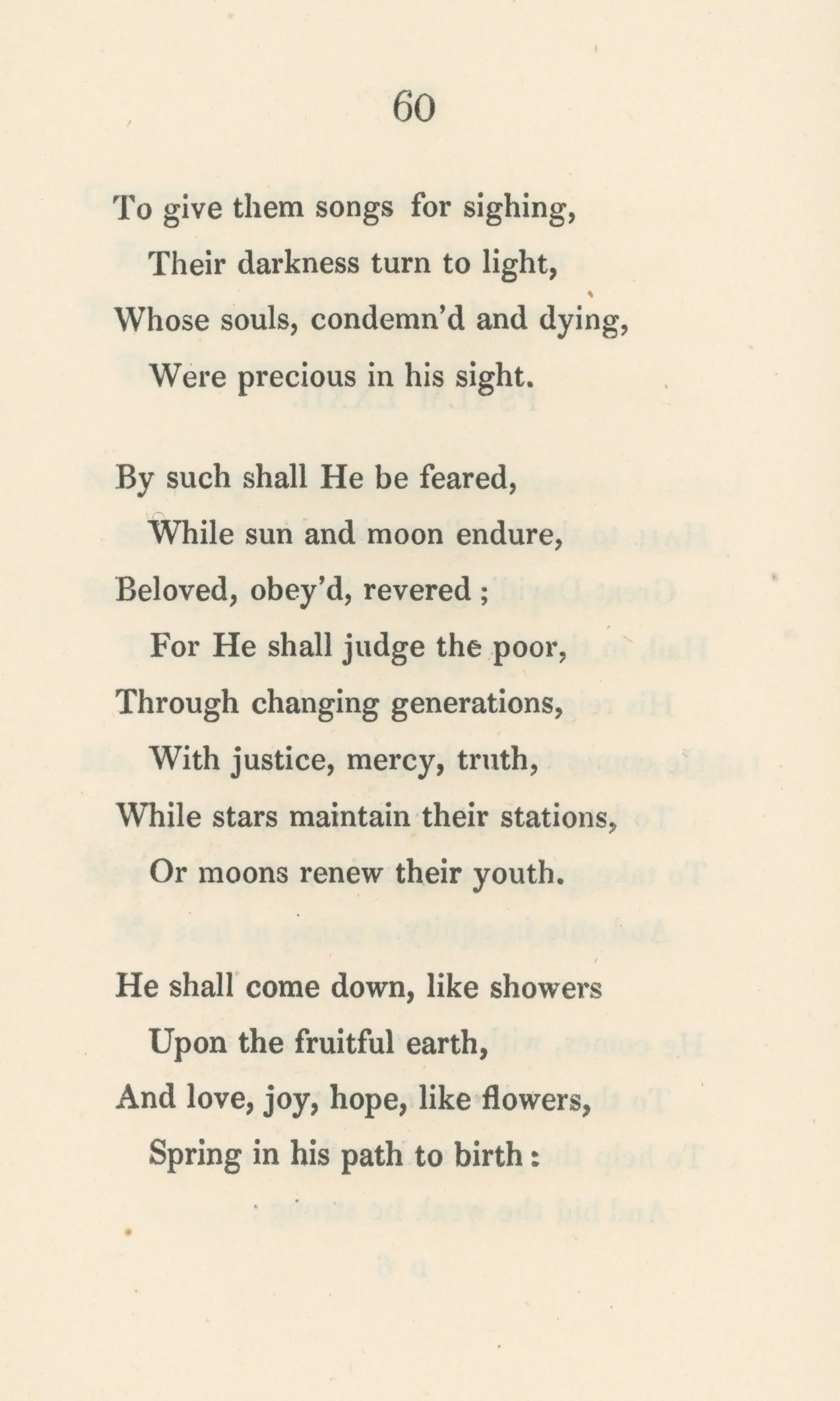

Regarding Montgomery’s own publication, the proof sheets for Songs of Zion were completed in May:

On his return to Sheffield, May 18, he found the proof sheets of his little volume of Songs of Zion awaiting him. . . . That some of these compositions are eminently beautiful, and, as such, will always be admired and sung, cannot be denied; that founded on the 72nd Psalm, for example, is one of the most mellifluous and perfect hymns in the language.[4]

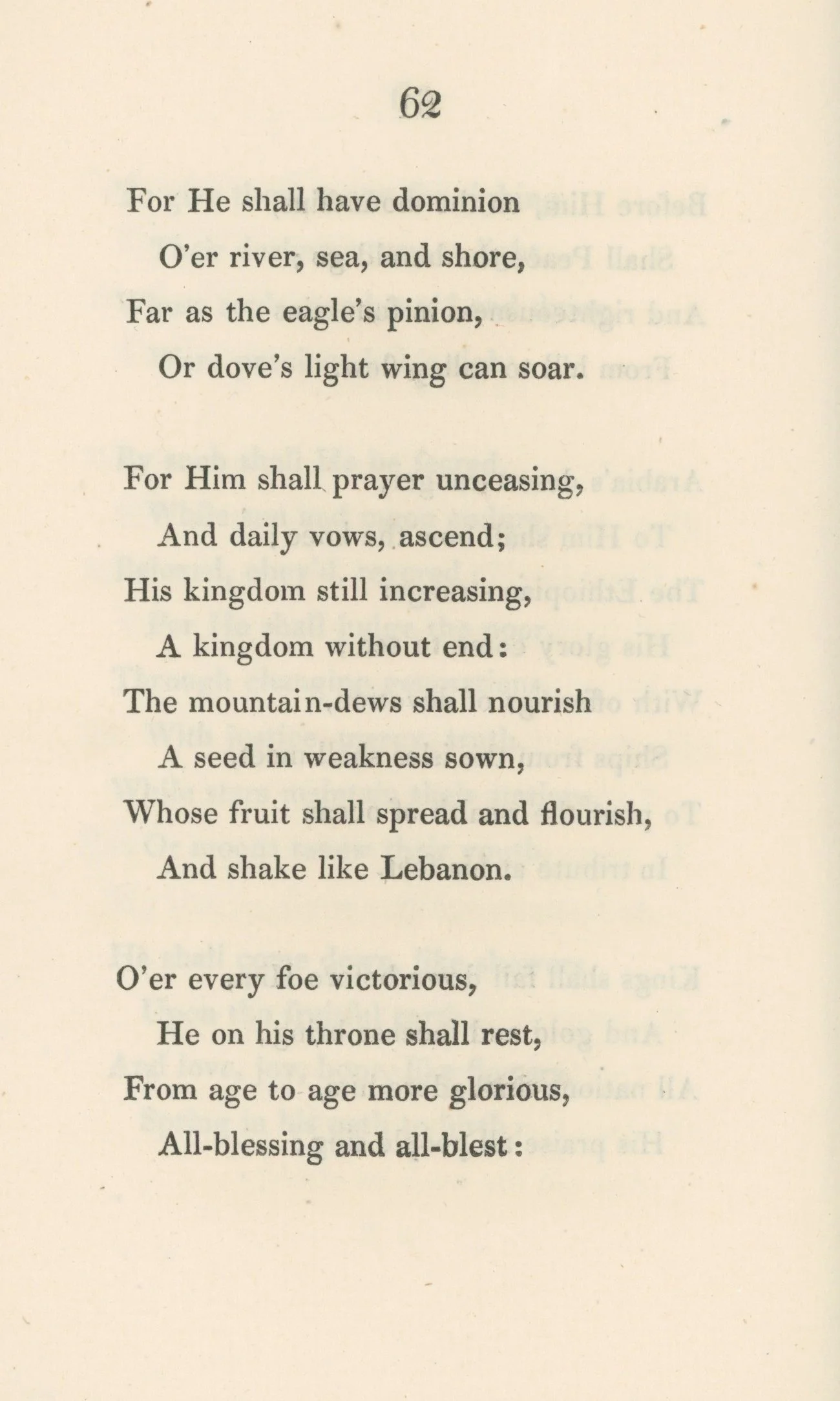

By the time the book went to press, Montgomery had changed the last line of his paraphrase to read “That name to us is—Love.”

Fig. 3. Songs of Zion, Being Imitations of the Psalms (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1822).

This hymn was later added to his Poetical Works, vol. 4 (Boston: T. Bedlington, 1825) and other subsequent collections, the last being his Original Hymns (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1853).

II. Text: Analysis

As stated above, Montgomery interpreted Psalm 72 as a prophetic psalm, although he did not go so far as to Christianize the psalm by invoking the name of Christ (as in Isaac Watts’ “Jesus shall reign where’er the sun”). He did, however, assert the fulfillment of the prophecy by declaring “His reign on earth begun.” In his approach, Montgomery generally included the language of the psalm without following the line-by-line progression of the psalm in the same order. For the locations mentioned in Psalm 72:10, he modernized the names, perhaps for greater familiarity to modern worshipers. Some insertions here include “incense,” reasonably inferred from 72:15, plus the poetic license of describing distance in terms of the range of eagles and doves. The final line, when Montgomery sets up an opportunity to name this person, settles on “Love,” possibly a nod to 1 John 4:8 (“God is love”) or any number of passages describing the love of Christ.

John Julian said, “Of all Montgomery’s renderings and imitation of the Psalms, this is the finest.”[5]

Albert Edward Bailey compared Montgomery to Watts and noted Montgomery’s loose approximation of the original:

It is evident at once that Montgomery has stuck less closely to his text than did Watts. In the early days before Watts broke the spell, such freedom would have been considered sacrilege, but in this period when literary form was more valued than faithfulness to the inspired Word, it was reckoned a virtue. Montgomery absorbed from the Psalm the essential intent of the Psalmist as he saw it, then proceeded to create his own imagery. “Songs for sighing,” “darkness turn to light,” condemned and dying,” and all last six lines have no parallel in the original.

This is less of a missionary hymn than one might expect. Watts stressed the universal extent of Christ’s kingdom, the gifts brought to the Lord from the ends of the earth, and gave the scene all the pageantry of an Indian durbar. Montgomery glorifies rather the redemptive function of Christ and the new social order that His justice will bring. His poem is more prayer than prophecy, or shall we say, it is the prophecy in large part unfulfilled but still capable of inspiring the Church to work for its fulfillment![6]

Faith Cook sees in this hymn a personal glimpse, Montgomery having been imprisoned twice for “seditious libel” on account of printing controversial comments against the government in his paper. “He writes with burning compassion for the ‘poor and needy’—which had placed him behind bars twice—expressing his fierce denunciation of the slave trade . . .”[7]

Literary scholar J.R. Watson observed similarities to other writers:

Montgomery, like Milton [in Paradise Lost], looks forward and back, increasing the significance of one event by seeing it in the context of others, and seeing the entry of Christ into human history as the transformation of a fallen world. It is this process of radiant transformation which is found in Montgomery’s paraphrase of Psalm 72. . . . It takes up the story where “Angels from the realms of glory” leaves off: the image of the freed captive echoes the breaking of chains (both show Montgomery’s debt to Charles Wesley’s physical metaphors). . . . The welcome for spring after winter is found in Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads, and most powerfuly of all in Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, where the captive is set free, the chains broken, and life-giving spring comes to warm the earth. It is not possible to find specific verbal echoes of Shelley in the hymn, but it is perhaps significant that Prometheus Unbound was published in 1820 and Montgomery’s paraphrase was written in 1821. . . . [The last line] is reminiscent of Charles Wesley’s “Wrestling Jacob,” especially in Montgomery’s earlier version—“His name—what is it? Love.”[8]

Given the hymn’s references to gold and incense, it is often associated with Epiphany.

Tunes

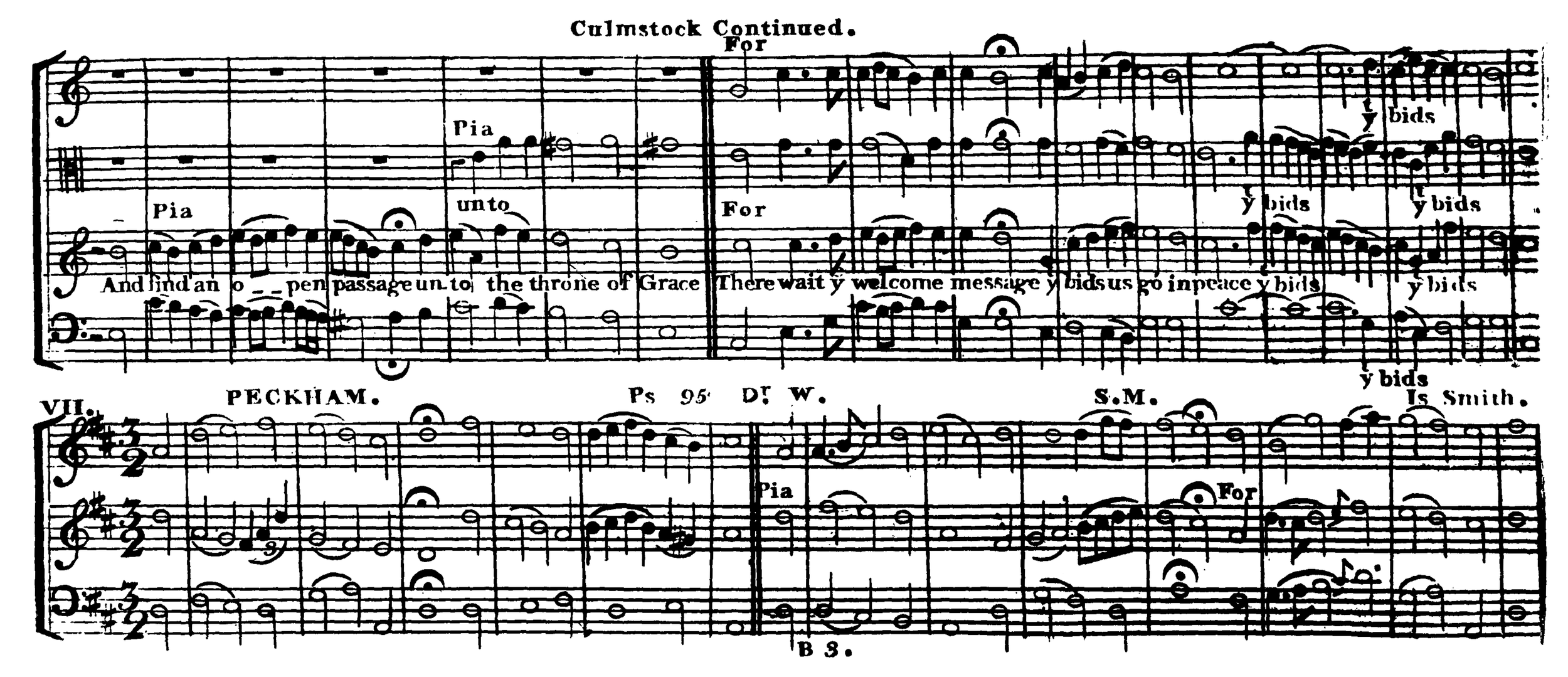

1. CULMSTOCK

When Montgomery’s text was printed in The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle it included a reference to the tune CULMSTOCK. The only tune by that name in tune books of the time was the tune by Thomas Walker (1764–1827), from John Rippon’s A Selection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes (London: John Rippon, 1792). CULMSTOCK is a repeating tune (a fuguing tune), with the melody in the third voice, and two passages of polyphony.

Fig. 4. A Selection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes (London: John Rippon, 1792).

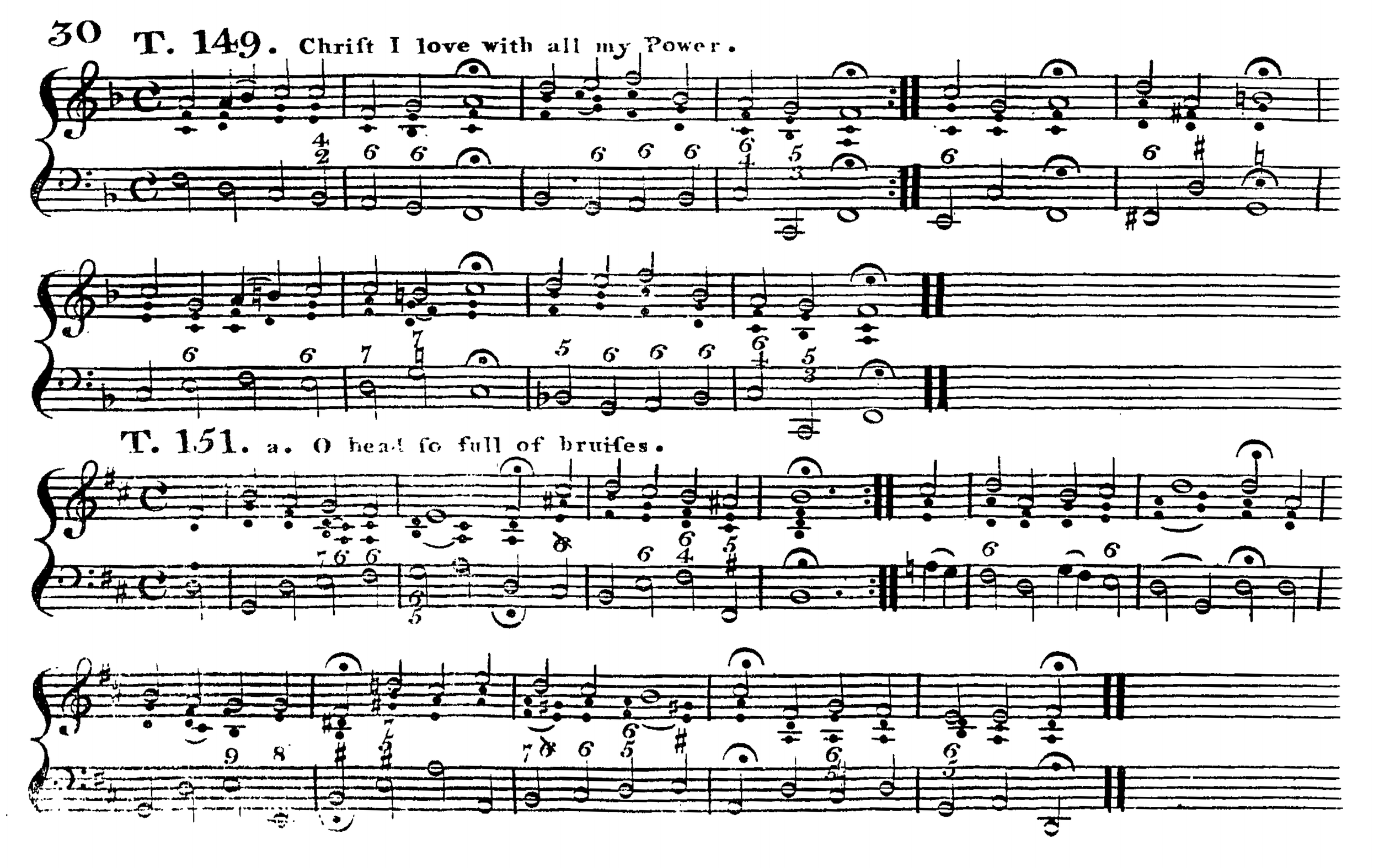

2. Moravian tunes

Moravian tune books from that time period did not use distinct names for tunes, only numbers indicating the classification of the meter, and representative first lines of texts. Montgomery’s meter was considered tune class no. 151. Representative Moravian tune books from this period were Hymn-Tunes Sung in the Church of the United Brethren (1790) and The Hymn Tunes of the Church of the Brethren (1824). The 1790 collection included three tunes in this tune class: 1. “O head so full of bruises,” better known as HERZLICH TUT MICH VERLANGEN (PASSION CHORALE); 2. “How shall I meet my Savior,” better known as VALET WILL ICH DIR GEBEN (ST. THEODULPH); and “Commit thou each thy grievance,” better known as ERMUNTERT EUCH IHR FROMMEN (REJOICE). The 1824 collection included these same tunes.

Fig. 5. Hymn-Tunes Sung in the Church of the United Brethren (London: Christian LaTrobe, 1790).

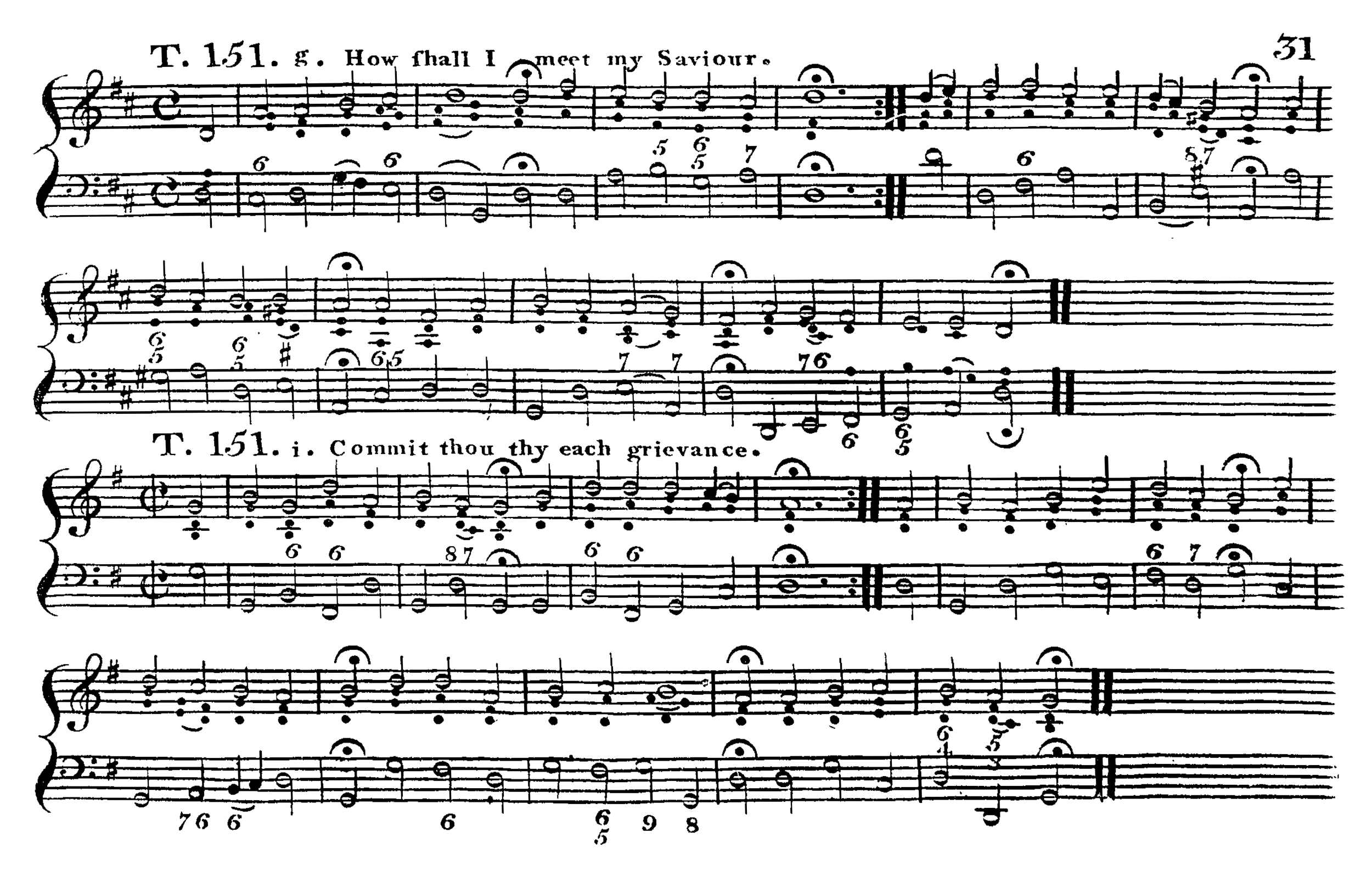

3. MISSIONARY HYMN

In the United States, one of the earliest tune settings was to this tune by Lowell Mason (1792–1872), written in 1824 for the hymn “From Greenland’s icy mountains” by Reginald Heber (1783–1826) and “first heard in divine service at the Independent Presbyterian Church, Savannah, GA, the composer as organist and director, leading the singing.”[9] It was published as sheet music ca. 1829 and included in his Choral Harmony (1830).

Fig. 6. Choral Harmony (Boston: Richardson, Lord and Holbrook, 1830).

When Lowell Mason included this tune in Spiritual Songs, No. 2 (1831) and the combined Spiritual Songs for Social Worship (1832), he included “Hail to the Lord’s anointed” as an additional text alongside Heber’s hymn.

Fig. 7. Spiritual Songs for Social Worship (Utica: Hastings & Tracy & W. Williams, 1832).

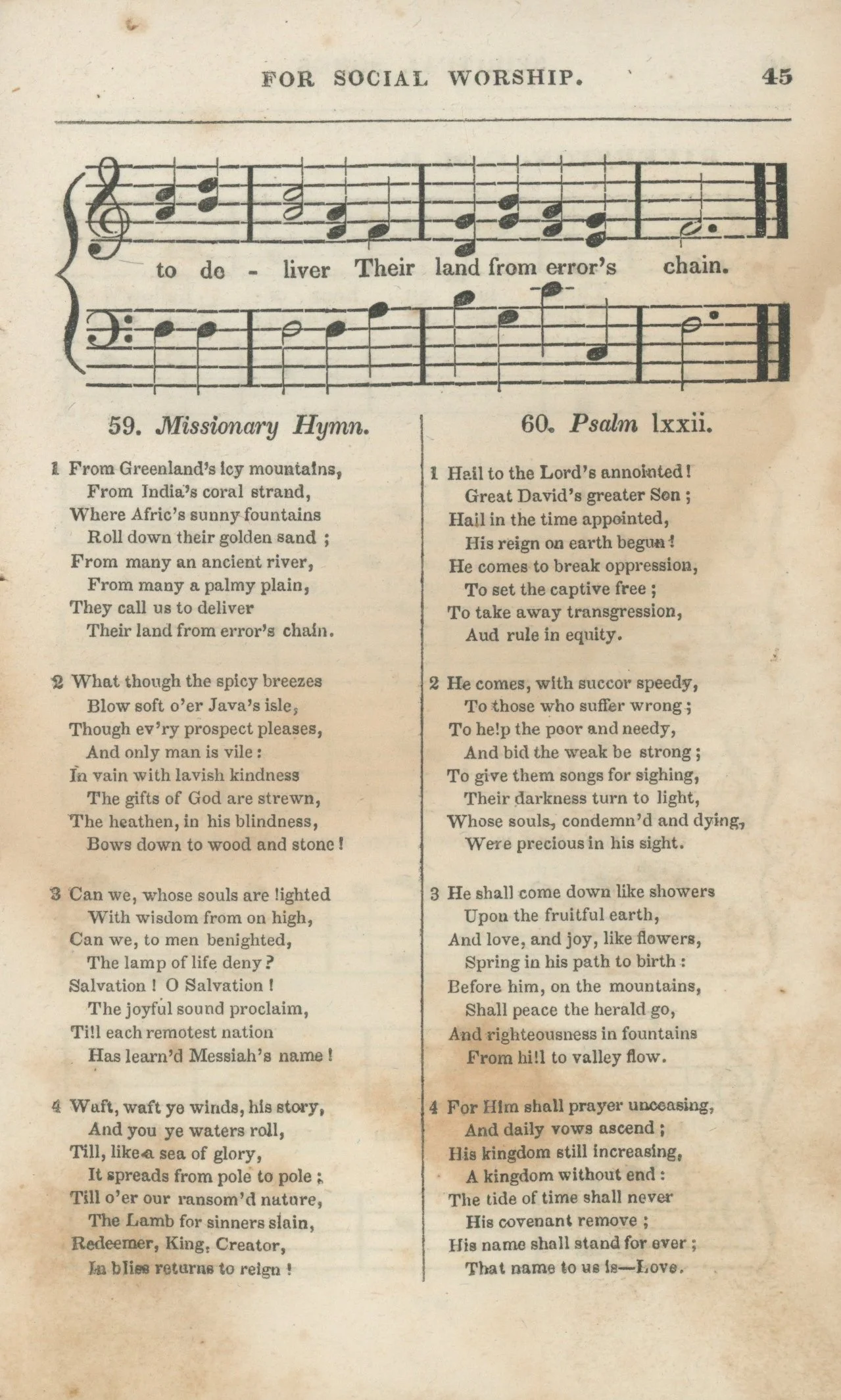

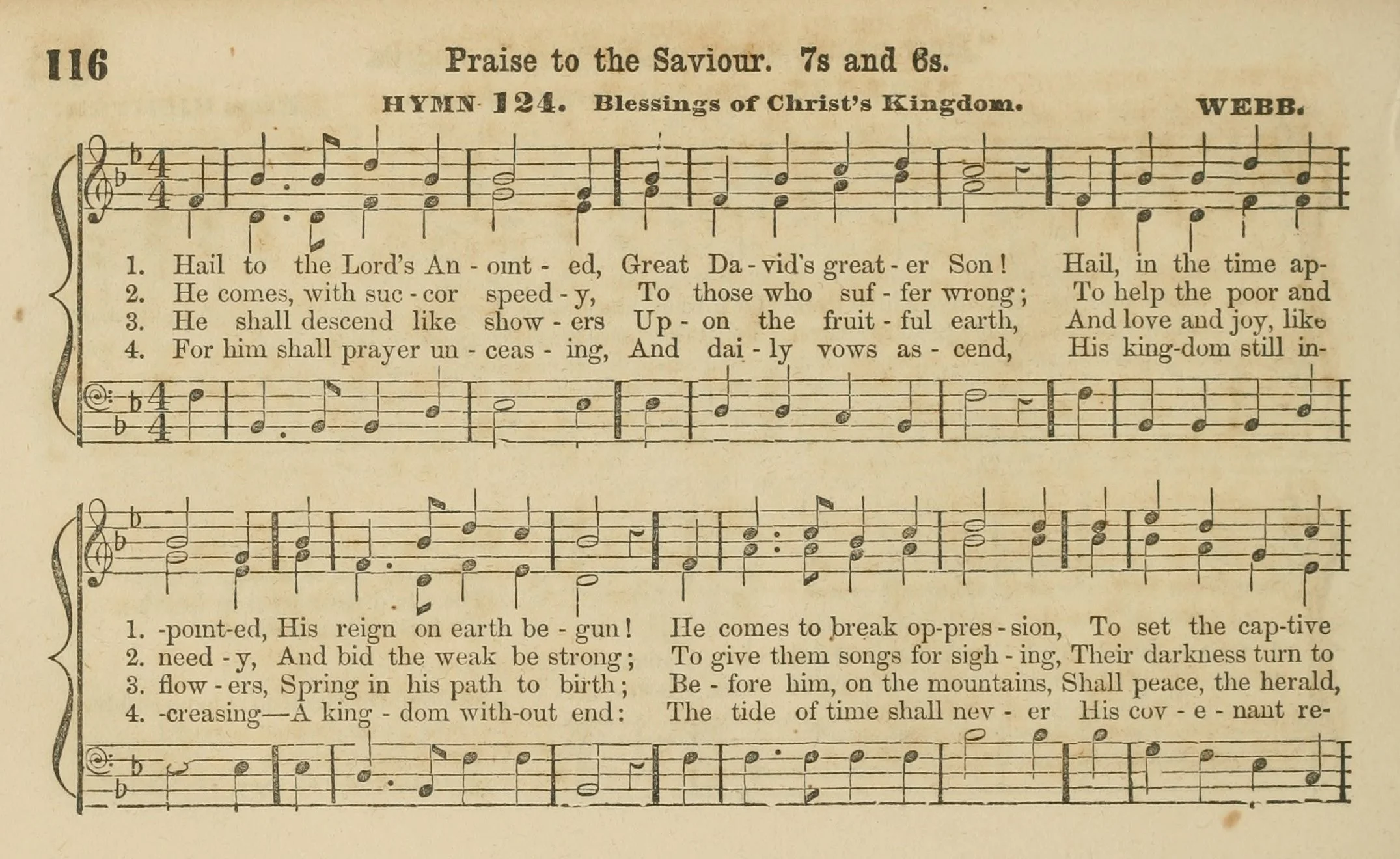

4. WEBB

Montgomery’s text has frequently been set to WEBB by George James Webb (1803–1887) as early as Bradbury’s Sunday School Melodies (1850) and more prominently in the Sabbath Hymn and Tune Book (1859).

Fig. 8. Bradbury’s Sunday School Melodies (NY: Ivison & Phinney, 1850).

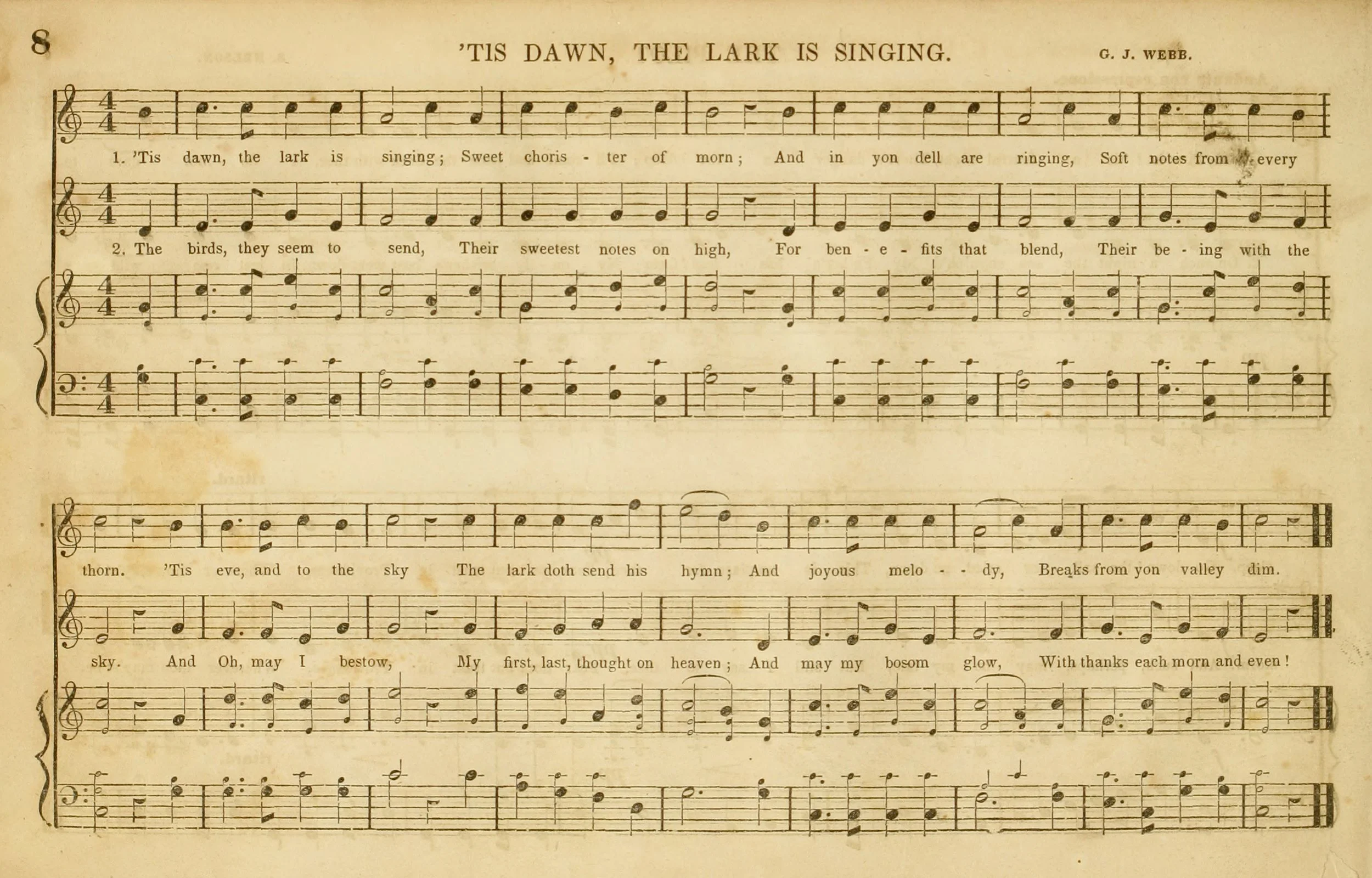

Webb’s tune was reportedly written on his voyage to emigrate from England to America in 1830.[10] It was first published in The Odeon (1837) where it had been set to “Tis dawn, the lark is singing.” In its earliest version, the fifth and seventh phrases carry only six syllables.

Fig. 9. The Odeon (Boston: J.H. Wilkins & R.B. Carter, 1837).

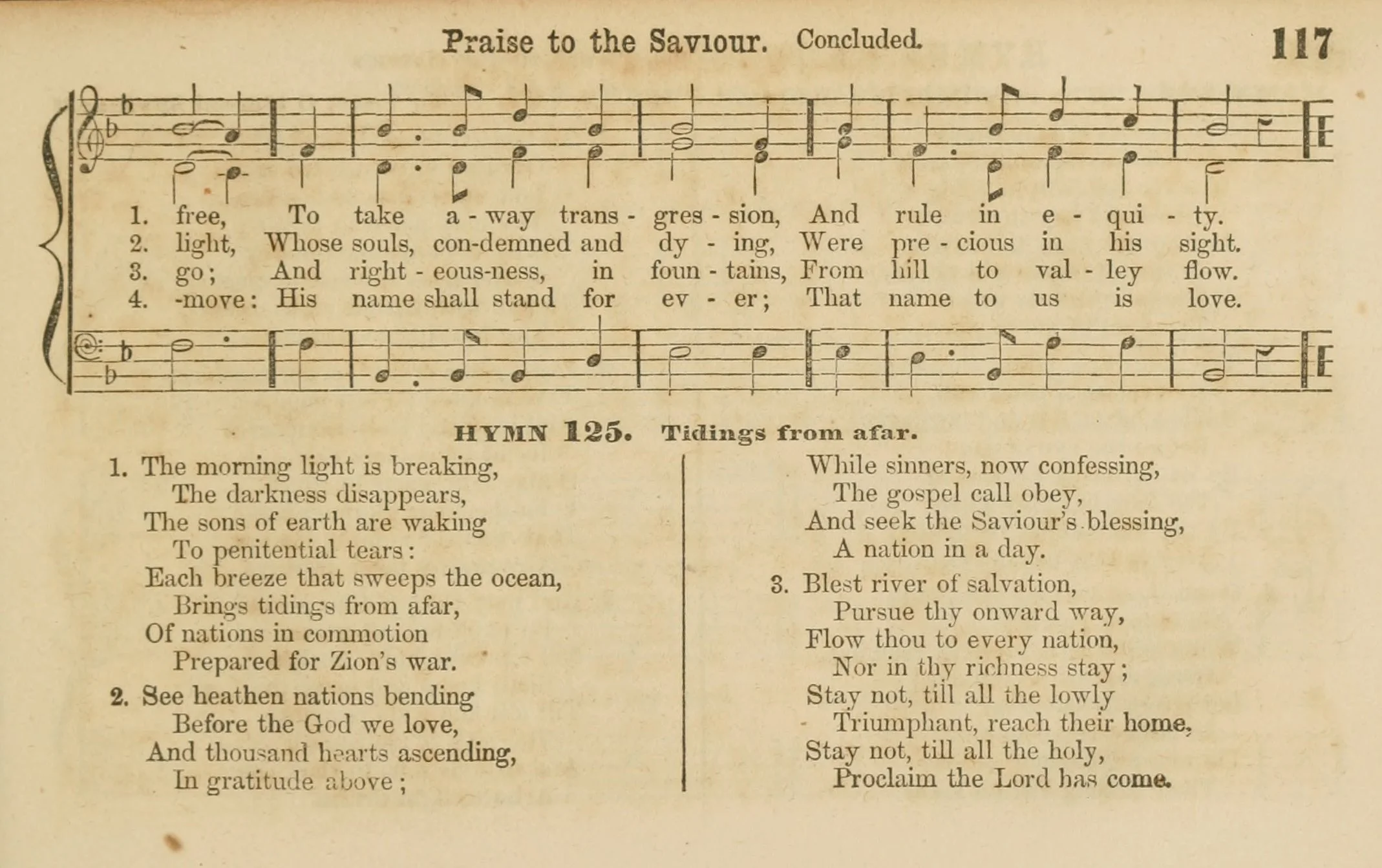

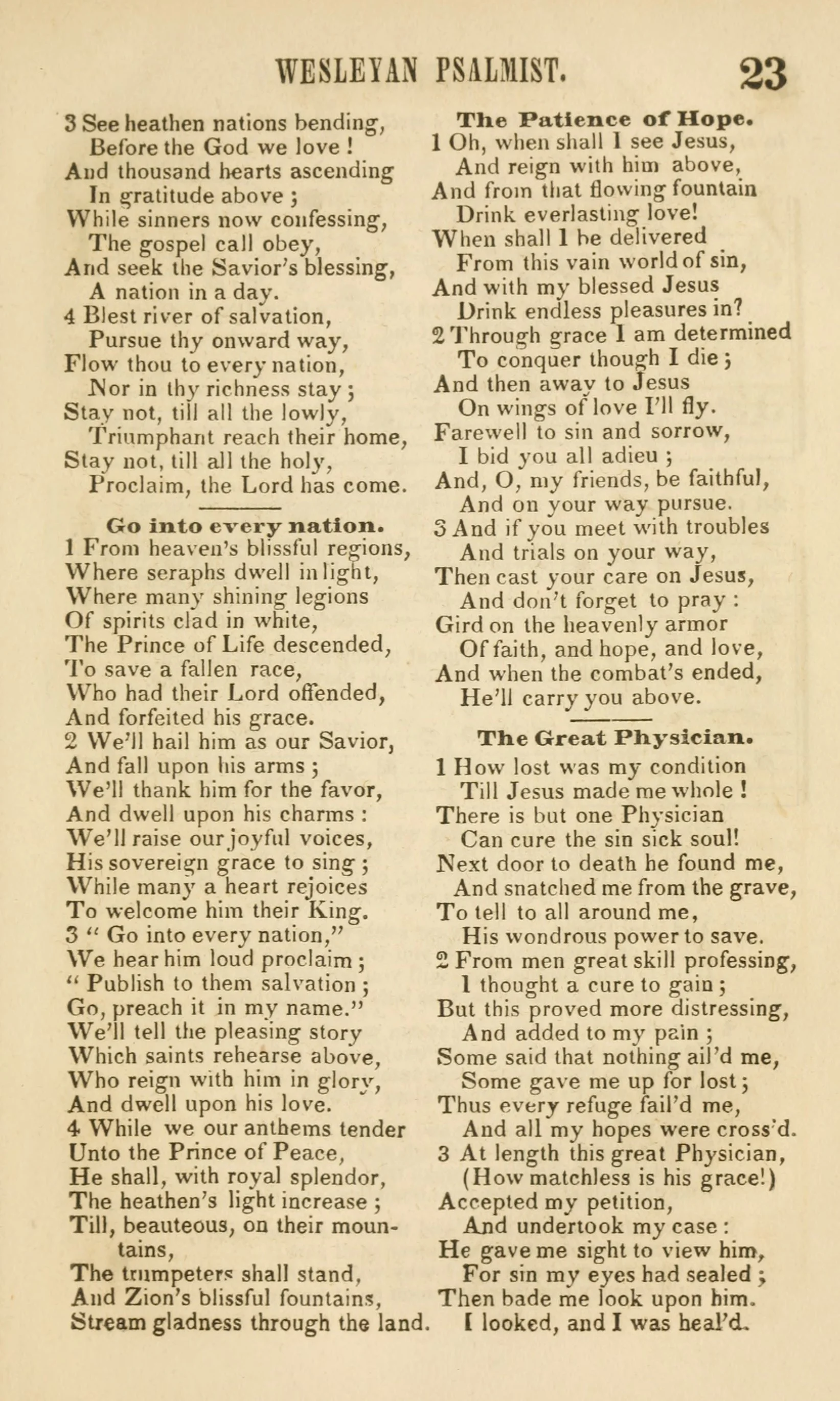

The adaptation of the tune into 7.6.7.6 D seems to have been made for The Wesleyan Psalmist (Boston: D.S. King, 1842), edited by M.L. Scudder, where it was set to “The morning light is breaking” by Samuel F. Smith (1808–1895). Here the tune was called MILLENNIAL DAWN and that name has been repeated in other collections.

Fig. 10. The Wesleyan Psalmist (Boston: D.S. King, 1842).

5. CRÜGER

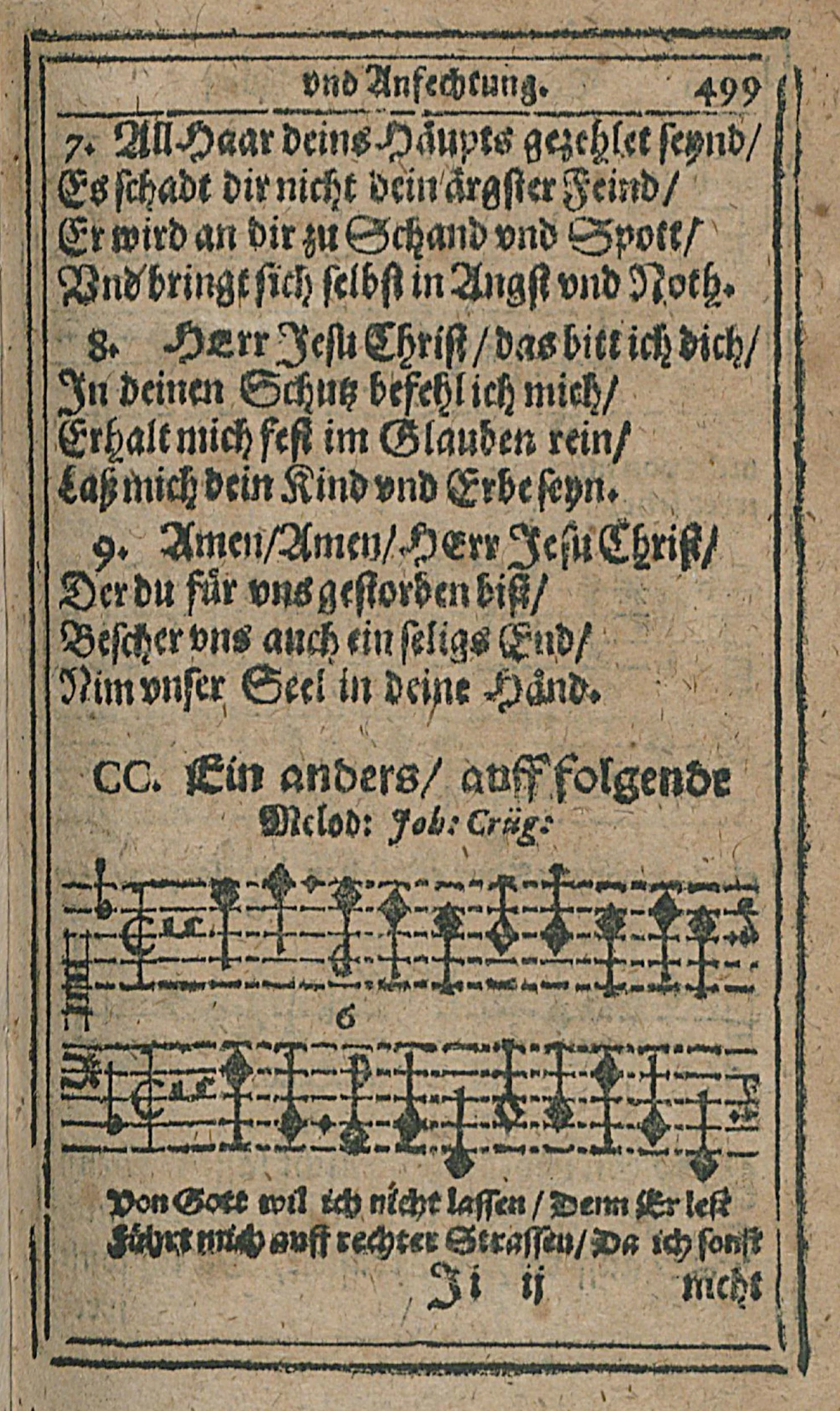

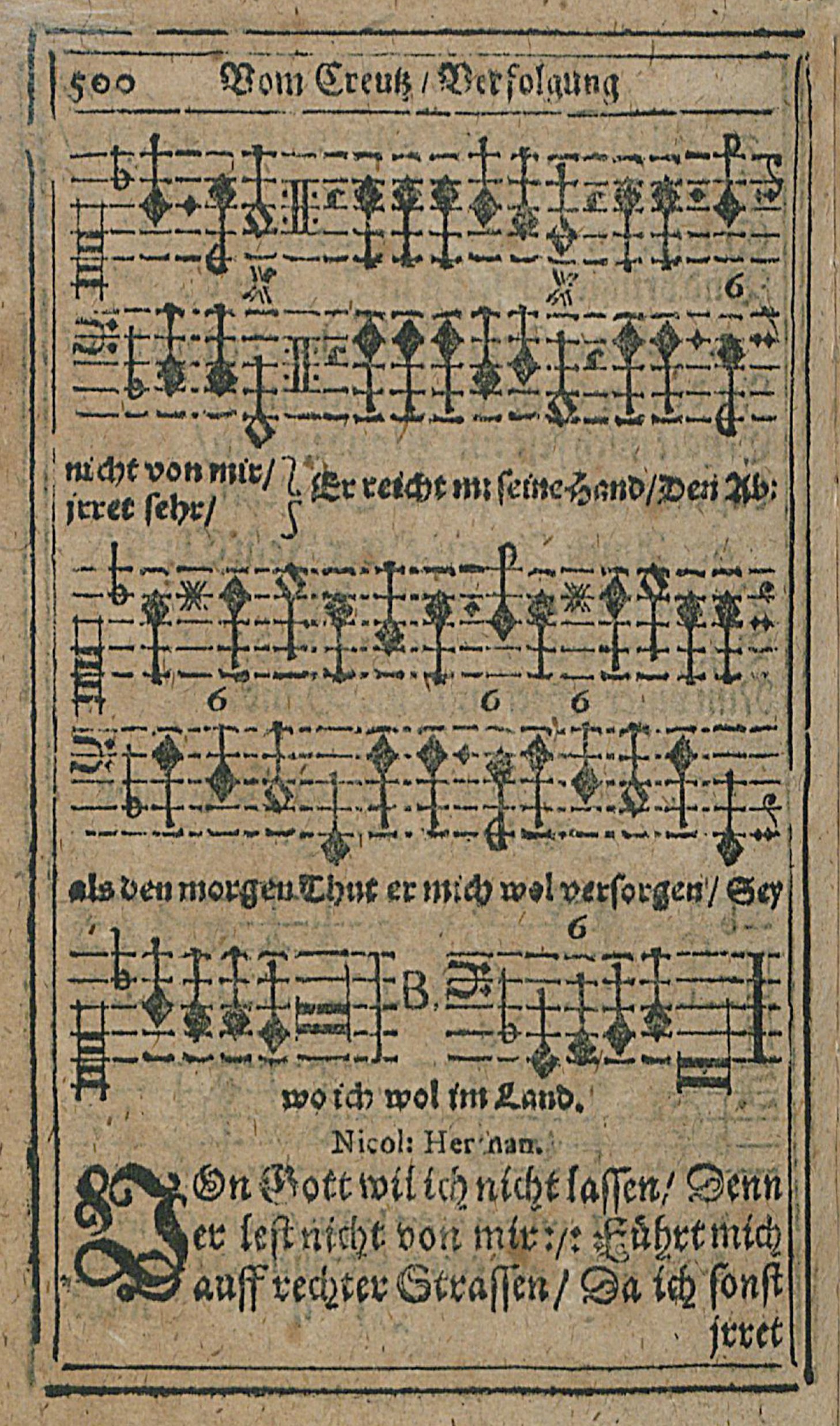

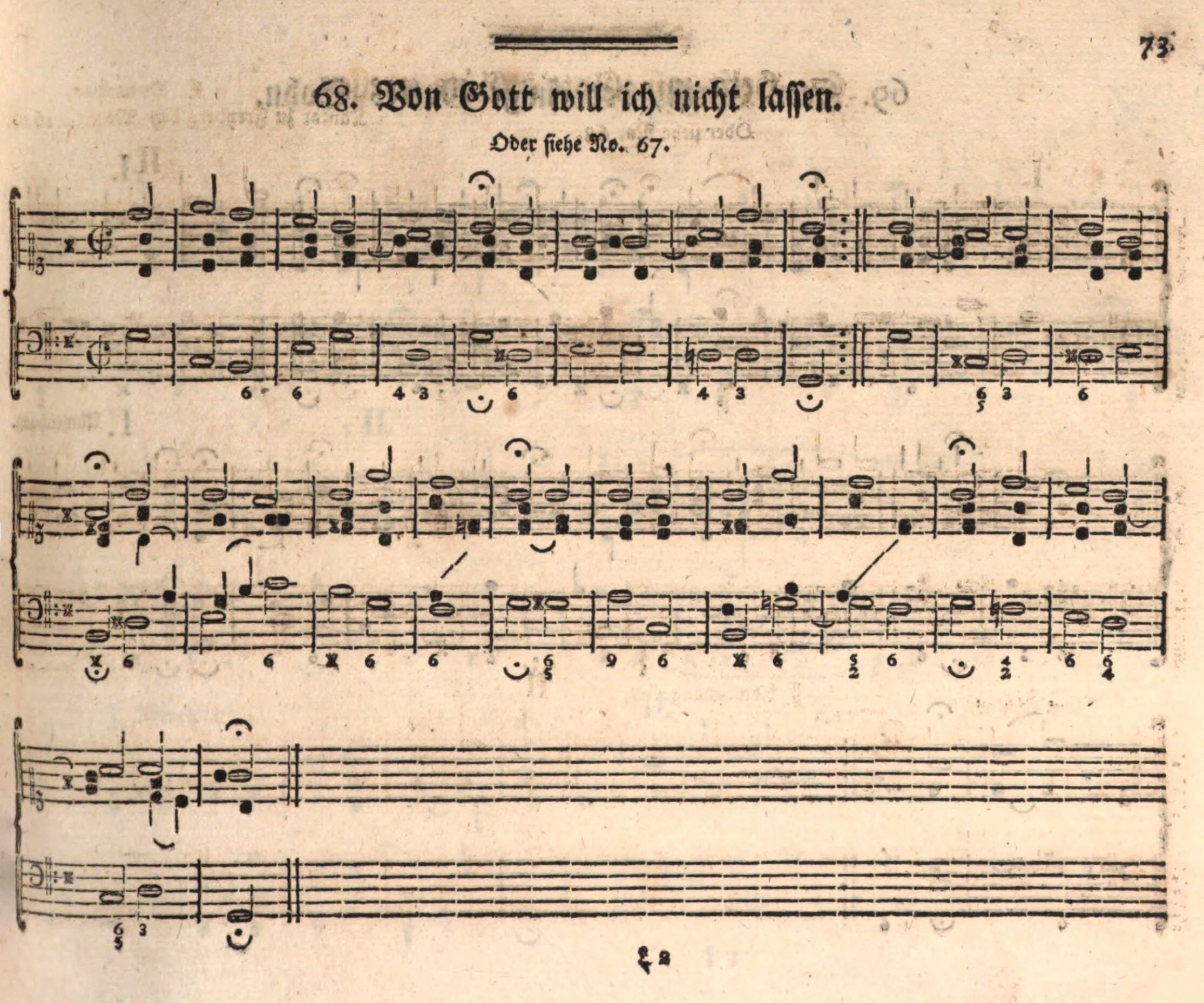

When Montgomery’s hymn was adopted into Hymns Ancient & Modern (London: Novello, 1861), it was set to CRÜGER, which is an adapted version of a tune by Johann Crüger (1598–1662) from Newes vollkömmliches Gesangbuch (Berlin: Runge, 1640), originally set to the text “Von Gott will ich nicht lassen,” credited there to Nikolaus Herman (1500–1561), but other sources credit it confidently to Ludwig Helmbold (1532–1598).[11] Crüger’s tune is not to be confused with an older tune associated with this text. This original score was given in two parts, melody and bass.

Fig. 11. Newes vollkömmliches Gesangbuch (Berlin: Runge, 1640).

A key variant of this tune was printed in Johann Christophe Kühnau’s Vierstimmige alte und neue Choralgesänge (Berlin: Kühnau, 1786). The alterations here are quite extensive, but the tune generally retains its cadential points of arrival, so it is still recognizable in comparison to the original.

Fig. 12. Vierstimmige alte und neue Choralgesänge (Berlin: Kühnau, 1786).

Kühnau’s version was adapted into English hymnody by William Henry Monk for Hymns Ancient & Modern (London: Novello, 1861). Monk’s version departs from Kühnau’s especially in the two phrases after the repeat.

Fig. 13. Hymns Ancient & Modern (London: Novello, 1861).

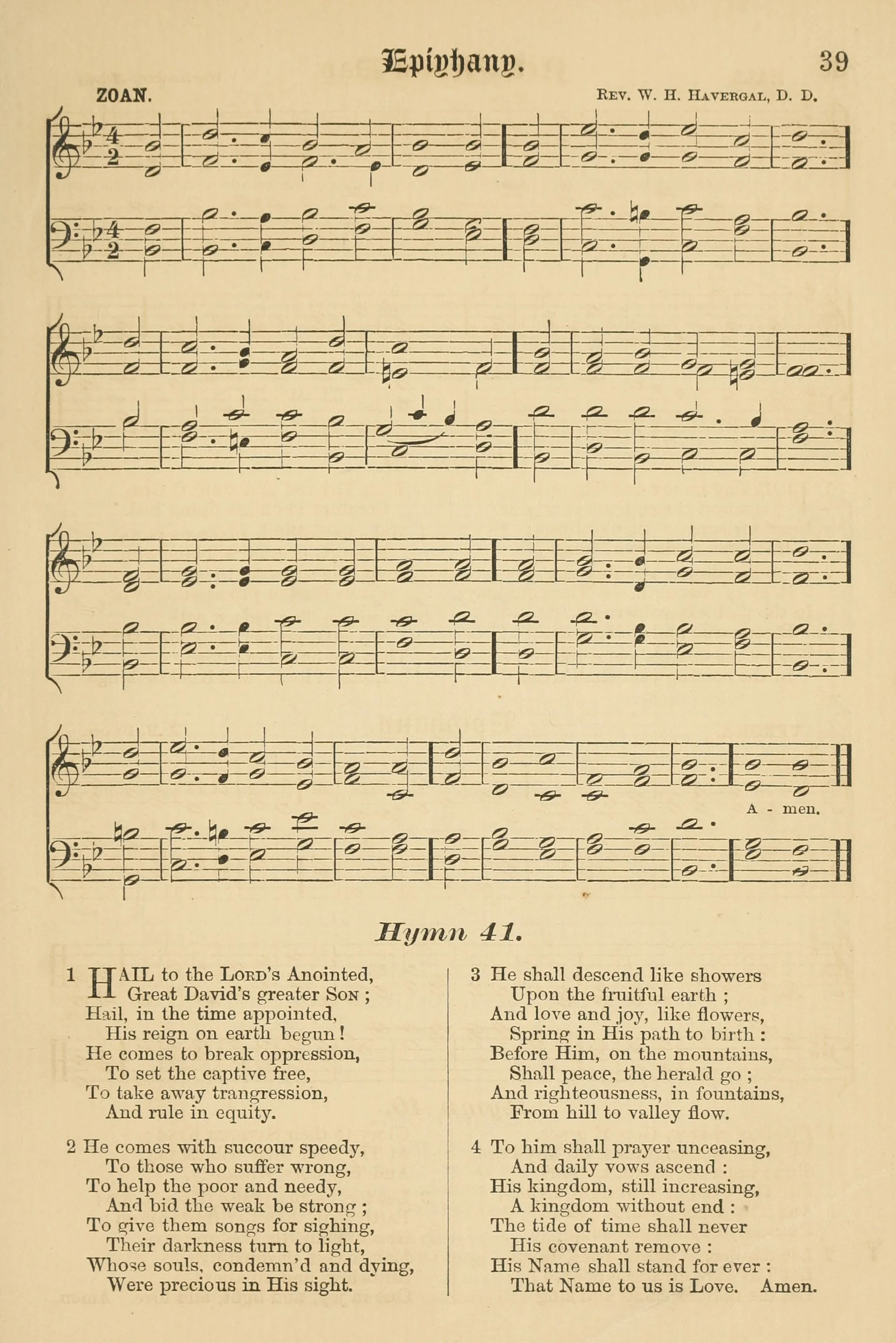

6. ZOAN

Another common tune pairing is with ZOAN by William Henry Havergal (1793–1870), from A Hundred Psalm and Hymn Tunes (1859). The tune is evidently named after the field in Egypt where some of God’s wonders were performed (Num. 13:22, Ps. 78:12,43), which is also known as Tanis. In the United States, the tune was first used with Montgomery’s text in J. Ireland Tucker’s The Parish Hymnal (NY: F.J. Huntington & Co., 1870). This pairing has been repeated in other Episcopal hymnals and elsewhere.

Fig. 14a. A Hundred Psalm and Hymn Tunes (London: Addison, Hollier, and Lucas, 1859).

Fig. 14b. The Parish Hymnal (NY: F.J. Huntington & Co., 1870).

7. Additional Tunes

Additional tune pairings in circulation include ELLACOMBE and AURELIA, which are better known with other texts. One popular pairing is with a tune known as WOODBIRD or it’s German incipit ES FLOG EIN KLEINS WALDVÖGELEIN, whose text can be found as early as 1600 in a pamphlet published in Augsburg by Valentin Schönigk, and whose tune was said by Franz Magnus Böhme to have been contained in a tablature book from Memmingen, although the location of that tablature book is presently unknown, and the folk song is better known by another tune.[12] SHEFFIELD (BRITISH GRENADIERS) is based on a British marching song from the 17th century, paired with Montgomery’s text as early as The New Church Hymnal (NY: Appleton, 1937). Lutheran hymnals use FREUT EUCH IHR LIEBEN CHRISTEN by Leonhart Schröter from Newe Weinacht Liedlein mit vier Vnd Acht Stimmen Componiret (1587) since this coupling in The Lutheran Hymnal (1941).

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

27 January 2026

Footnotes:

John Julian, “Hail to the Lord’s anointed,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (London: J. Murray, 1892), p. 480: HathiTrust; citing Church Hymnal Set to Appropriate Tunes (Dublin: APCK, 1891), p. 16: Archive.org

John Holland & James Everett, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of James Montgomery, vol. 3 (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1855), p. 278: HathiTrust

John Holland & James Everett, Memoirs, vol. 3 (1855), p. 284: HathiTrust

John Holland & James Everett, Memoirs, vol. 3 (1855), p. 288: HathiTrust

John Julian, “Hail to the Lord’s anointed,” A Dictionary of Hymnology (1892), p. 480: HathiTrust

Edward Albert Bailey, The Gospel in Hymns (NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950), pp. 157–158.

Faith Cook, Our Hymn Writers and Their Hymns (Carlisle, PA: EP Books, 2005), p. 257.

J.R. Watson, The English Hymn (Oxford: University Press, 1997), pp. 313–314.

Henry L. Mason, Hymn-Tunes of Lowell Mason (Cambridge, MA: University Press, 1944), p. 23.

Theron Brown & Hezekiah Butterworth, The Story of the Hymns and Tunes (NY: American Tract Society, 1906), p. 182: Archive.org

See for example Paul Heiser & Joseph Herl, “From God can nothing move me,” Lutheran Service Book Companion to the Hymns, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), pp. 985–988.

Frauke Schmitz-Gropengiesser, “Es flog ein klein Waldvögelein der Liebsten vor die Tür” (2008), Populäre und traditionelle Lieder: Historisch-kritisches Liederlexikon: http://www.liederlexikon.de/lieder/es_flog_ein_kleines_waldvoegelein_der_liebsten_vor_die_tuer

Related Resources:

Maurice Frost, “Hail to the Lord’s anointed,” Hymns Ancient & Modern Historical Companion (London: William Clowes & Sons, 1962), pp. 263–264.

Frank Colquhoun, A Hymn Companion: Insight into 300 Christian Hymns (Wilton: Morehouse Barlow, 1985), p. 69.

“Hail to the Lord’s anointed,” Hymnary.org: https://hymnary.org/text/hail_to_the_lords_anointed