This Little Light of Mine

I. Recorded History

This African American spiritual or early gospel song emerged into public consciousness via a recording by the Louisville Sanctified Singers. The song “God give me a light” was recorded on 14 June 1931 for Victor Records 23287, performed by four female and five male singers (including “Mrs. Hayes and Miss Davis”), accompanied by a rhythmically strummed guitar and tambourine. In this recording, the words are as follows:

God give me a light, oh, will you let it shine?

God give me a light, oh, will you let it shine?

God give me a light, oh, will you let it shine?

Let it shine, shine, shine, shine.

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine . . .

In my little home, I’m gonna let it shine . . .

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine . . .

God give me a light, oh, will you let it shine? . . .

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine . . .

In my little home, I’m gonna let it shine . . .

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine . . .

The music follows an implied 16-bar structure. The leader intones the fifth of the scale degree then descends to 1; the second phrase stays around 1, then the third phrase starts on 3, outlining a I-IV-I chord sequence in the first three phrases, followed by a turnaround.

That same year, a month earlier, the song was mentioned in an announcement by pastor H.D. Prowd of Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church, Los Angeles, in the California Eagle newspaper, 8 May 1931, saying, “Deacon Price using Deaconess Anderson’s song, ‘This little light of mine,’ gave us a real blessing.” The distant appearance of this song in Los Angeles and Louisville just weeks apart indicates its widespread proliferation prior to 1931.

The next two oldest recordings were collected by John A. Lomax for the Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk Song (AFS 199-B, AFS 2648-B1).

On or around 9 April 1934,[1] Lomax recorded Jim Boyd at the State Penitentiary in Huntsville, Texas. Boyd’s version begins with the more familiar text, “This little light of mine,” followed by “Everywhere I go,” “Round these prison walls,” “God, he give it to me,” “This little light of mine,” “In my daily walk,” and “In my daily talk.” Like the Louisville version, Boyd’s rendition has a brisk tempo with a persistent rhythm. Melodically, Boyd’s rendition starts by hovering on the third scale degree and dips down to 1, then goes up to the subdominant 4 before returning to the original shape, ultimately yielding a consistent 16-bar structure. This version has been transcribed by Gail Needleman for the Kodály Center at the University of Redlands.

Fig. 1. “This little light of mine,” Kodály Center transcription, excerpt.

John and Ruby Lomax recorded Doris McMurray at Gorree State Farm near Huntsville, Texas, on 14 May 1939. McMurray’s rendition includes verses “This little light of mine,” “Everywhere I go,” “In my neighbor’s home,” and “This little light of mine.” Melodically, the melody starts on the fifth scale degree and falls to 1; the second phrase outlines a IV chord, much like Boyd’s version, then returns to the original shape. It has a consistent16-bar structure.

Fig. 2. “This little light of mine,” Kodály Center transcription, excerpt.

An extra verse or bridge section, “Monday gave me the gift of love,” and “The light that shines is the light of love,” etc., was composed by folk singer Bob Gibson (1931–1996), recorded on his album There’s a Meetin’ Here Tonight (Riverside Records, 1958). Gibson also performed the song for the Newport Folk Festival, 24–26 June 1960, programmed among other folk legends like Pete Seeger, John Lee Hooker, Lester Flatt, and Earl Scruggs (issued on The Newport Folk Festival 1960 Vol. 2, Vanguard VRS 9084). Gibson’s additions to the song were registered for copyright on 27 October 1960. His version came to prominence in the Civil Rights Movement, included in songbooks like We Shall Overcome! Songs of the Southern Freedom Movement (NY: Oak Publications, 1963), where his extra words were credited to him. From the reverse of his 1958 album:

Bob’s repertoire has always included Negro spirituals, jubilees, and gospel songs, and this album has a liberal representation of such selections. These, too, tend to be songs that celebrate hope and faith, despite the fact that they originated with poor, hard-working, oppressed people. They also tend to be songs that call for, and take full advantage of a surging rhythmic beat such as is provided by the three instrumentalists here . . .

II. Published History

The earliest confirmed publication of the song was in Twelve Negro Spirituals for Men’s Voices (Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1937), edited by Philadelphia musician Frances Albert Clark (1867–1948). In this example, the melody of the chorus is in the second voice, whereas the melody for the verse is in the top voice. Compared to other early versions, this one is unique in the way the second phrase ends with “shine, shine, shine and shine,” and the fourth includes “Shine, shine, shine like the Morning Star,” a possible allusion to Revelation 22:19.

Fig. 1. Twelve Negro Spirituals for Men’s Voices (Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1937).

In his preface, Clark gave the following explanation of how he gathered the songs:

I am one of the first generation born out of slavery. From earliest childhood I heard these songs, sung by my elders (who had all their lives been held in slavery in various sections of the great Southland) as they gathered, almost nightly, in our home and in the homes of our kindred and friends. Here their chief diversion was telling their “religious experiences” and singing with sincere fervor these songs. Later in life, I heard them sung by church congregations, singing bands, traveling “Evangelists,” and quartets, during many months of work and travel through the great black belt.

Different sections and localities had their own variants in melody, harmony, and words, each group claiming theirs as the “right” version. I have been unable to find any authentic version of these songs. Certainly at the time of their origin, and earlier singing, they were not set down in musical notation. It follows naturally that there are many different presentations. In this collection, I have written them down as nearly as possible as I heard them.

The words to Clark’s verse are from an anonymous hymn beginning “One day as I was walking / Along a lonesome road,” found as early as Shaffer’s Pilgrim Songster (Zanesville, OH: Parke & Bennett, 1848), edited by Stephen D. Shaffer. In his preface, Shaffer credited the Methodist tradition with giving rise to many of the songs in his collection.

Fig. 2. Shaffer’s Pilgrim Songster (Zanesville, OH: Parke & Bennett, 1848).

The words in Clark’s 1937 arrangement most closely resemble the version printed in Marshall W. Taylor’s A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies (Cincinnati: Marshall W. Taylor & W.C. Echols, 1882). Taylor’s version includes a melody, the first part of which resembles the opening phrase of Clark’s version, but the back half is very different.

Fig. 3. A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies (Cincinnati: Marshall W. Taylor & W.C. Echols, 1882).

The first two lines of this text appeared in the Journal of American Folklore, vol. 10 (1897), p. 116, collected from Emma M. Backus in Columbia County, Georgia, with the refrain “Rockaway home to Jesus”:

One day I wuz a walkin’

Long dat lonesome road

King Jesus spoke unto me

An’ lifted off de load.

Rockaway, rockaway, rockaway,

Rockaway home to Jesus.

These lines appeared again in the Journal of American Folklore, vol. 26 (1913), p. 162, with a different refrain, “We’ll wait on de Lawd,” collected from an unknown singer in Virginia:

One day ez I wuz walkin’

Along dat lonesome road

My hahuht wuz filled wid rapture

An’ I hyeuhd de voice uv Gawd.

We will wait on de Lawd, we’ll wait, we’ll wait,

We’ll wait on de Lawd.

The lines “If I am a Christian, I am the least of all,” as given in Taylor (1882) and Clark (1937) also appeared in early printings of “Go, tell it on the mountain.” These examples point to Clark’s verse as being part of a wandering stanza, similarly to how “When we’ve been there ten thousand years” came to be associated with “Amazing grace.” That is to say, the verse in Clark’s example is not exclusive to “This little light of mine” and seems to have developed separately. Clark’s verse is uncommon in earlier and later printings and recordings of the song.

The next earliest printing of “This little light of mine” appeared in Bowles Favorite Frye’s Special Gospel Song Book No. 6 (Chicago: Bowles Music House, 1940). The title is in reference to Chicago publisher Lillian M. Bowles (1885–1962) and musician Theodore Frye (1899–1963). In this example, the arrangement is by Charles Henry Pace (1886–1963), and the song was “Selected and Revised” by Lillian Bowles. This version has five stanzas of unequal syllables, the first three of which are consistent with the earliest recordings (as above). The copyright is dated 1934, making it presumably older than Clark’s arrangement, except the song did not appear in the previous five issues of the series. It could have been printed in leaflets. The song was not properly registered with the Library of Congress, so no secondary confirmation is available. Melodically, this version most closely resembles the recording by Doris McMurray (1939).

This arrangement was repeated in the New National Baptist Hymnal (1977, 2001), without credit to Pace.

Fig. 4. Bowles Favorite Frye’s Special Gospel Song Book No. 6 (Chicago: Bowles Music House, 1940).

A choral arrangement by John W. Work III (1901–1967) of Fisk University was published in 1943, and a version for solo voice followed in 1945.

The song crossed racial lines when it was arranged by Harry Dixon Loes (1892–1965) of the Moody Bible Institute for Gospel Songs Choruses No. 3 (Singspiration, 1943). Loes’ version introduces several stanzas not previously found elsewhere, such as “Hide it under a bushel? No!” “Won’t let Satan blow it out,” “Shine it over *Chicago, yes!” and “Let it shine till Jesus comes.” Loes has often been erroneously credited with writing the song.

Fig. 5. Gospel Songs Choruses No. 3 (Singspiration, 1943).

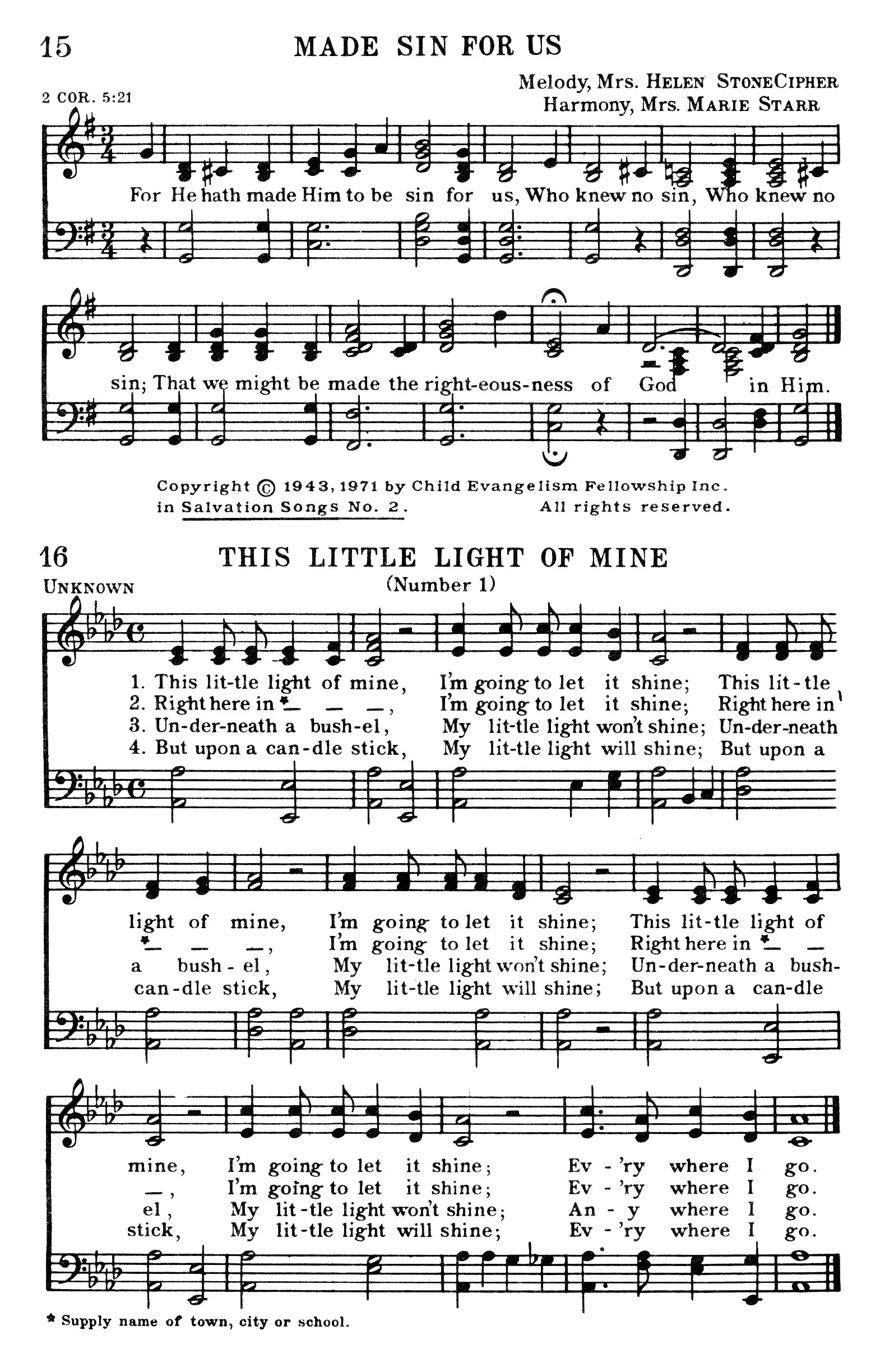

The version of the melody with an ascending incipit, 5–6–1, can be found in Salvation Songs for Children No. 2 (Warrenton, MO: Child Evangelism Fellowship Press, 1976), compiled by Ruth P. Overholtzer, but this variant is probably older. The arrangement here is uncredited.

Fig. 6. Salvation Songs for Children No. 2 (Warrenton, MO: Child Evangelism Fellowship Press, 1976).

Other arrangements in common use include ones by Cleavant Derricks for Golden Songs of Glory (1975), William Farley Smith for The United Methodist Hymnal (1989), Horace Clarence Boyer for Lift Every Voice and Sing II (1993), and Nolan Williams Jr. for the African American Heritage Hymnal (2001).

The song is often classified as a spiritual, but its 16-bar structure and AAAB textual pattern put it in line with similar twentieth-century, post-bellum gospel songs, such as “Glory, glory, hallelujah,” “I will trust in the Lord,” “Come and go with me to my Father’s house,” and “I woke up this morning with my mind stayed on Jesus.”

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

9 October 2025

Footnotes:

In the Library of Congress catalog card, this is dated June 1934, but Dixon et al. (1997) regarded this date as “unlikely” and preferred the date of April on the basis of Jim Boyd’s other recording, “If I got my ticket, Lord,” and Lomax’s known sequence of travel.

Related Resources:

Jim Boyd, “This little light of mine” (1934), Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/afc9999005.635/

Jim Boyd, “This little light of mine” (1934), transcribed by Gail Needleman, Kodály Center at the University of Redlands: https://kodalycollection.org/song.cfm?id=673&title=This%20Little%20Light%20of%20Mine%20

Doris McMurray, “This little light of mine (1939), Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/afc9999005.8332/

Doris McMurray, “This little light of mine” (1939), transcribed by Gail Needleman, Kodály Center at the University of Redlands: https://kodalycollection.org/song.cfm?id=1121&title=This%20Little%20Light%20of%20Mine%20#2

Discography of American Historical Recordings: https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/108477/Louisville_Sanctified_Singers

Robert M.W. Dixon, et al. Blues and Gospel Records, 1890–1943, 4th ed. (Oxford: University Press, 1997): Amazon

C.M. Hawn, “This little light of mine,” Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology:

http://www.hymnology.co.uk/t/this-little-light-of-mine