An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ

Salvation comes by Jesus Christ alone

with JUPITER

I. Background and Printing

Jupiter Hammon was born 11 October 1711 to two slaves and seems to have spent his entire life on the estate of Henry Lloyd and his descendants on Long Island, New York, including work as a clerk and a bookkeeper, with the exception of living in Hartford, Connecticut, during the Revolutionary War. He is known to have authored several published works, including An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York (1787). His earliest work—the earliest known hymn by an African American—is “An Evening Thought. Salvation by Christ, with Penetential Cries: Composed by Jupiter Hammon, a Negro belonging to Mr. Lloyd, of Queen’s Village, on Long Island, the 25th of December, 1760,” printed on broadsheets. At least one copy survives in the holdings of the New York Historical Society.

Fig. 1. “An Evening Thought,” Jupiter Hammon, broadside, New York Historical Society.

II. Textual Analysis

Hammon’s poem was written in abab quatrains but without visible line breaks, primarily in iambic common meter (8.6.8.6), with some exceptions, running to 88 lines, or 22 quatrains. It represents an orthodox theology, with a belief in exclusive salvation, as in Acts 4:12 (“Salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to mankind by which we must be saved,” NIV) or John 14:6 (“Jesus answered, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me,’” NIV). It also proclaims a belief in only one God (“The true and only One”), in the manner of three persons (trinitarian), with all three being evoked. There is one apparent Scripture quotation, “Ye shall not cry in vain,” although this is not a direct quote; it is possibly a reference to Psalm 9:12 (“He does not forget the cry of the humble,” NKJV). Another near-direct quotation is in the line “Ho! every one that hunger,” which is from Isaiah 55:1 in the KJV. Also embedded in this hymn is a belief in salvation by mercy, by redemption through the blood of Christ.

Regarding the first two lines of the second column, “Lord, turn our dark, benighted Souls; Give us a true motion,” Cedrick May, the most recent editor of Hammon’s works, suggests:

Hammon is making a comparison between the motion of the planets and other heavenly bodies similar to the way eighteenth-century natural philosophers would have imagined them, as well as the motion by which a Christian god moves the human soul.[1]

Hammon’s work A Winter Piece: Being a Serious Exhortation, with a Call to the Unconverted (1782) is a lengthy spiritual plea to unconverted souls. Part of his argument was as follows:

My brethren, in the first place, I am to show what is meant by coming to Christ labouring and heavy-laden. We are to come with a sense of our own unworthiness, and to confess our sins before the most high God, and to come by prayer and meditation, and we are to confess Christ to be our Saviour and mighty Redeemer. Matthew x, 33. Whosoever shall confess me before men, him will I confess before my heavenly Father. Here, my brethren, we have a great encouragement to come to the Lord and ask for the influence of his Holy Spirit, and that he would give us the water of eternal life, John iv. 14. Whosoever shall drink of this water as the woman of Samaria did, shall never thirst, but it shall be in them a well of water springing up to eternal life, then we shall believe in the merits of Christ, for our eternal salvation, and come labouring and heavy-laden with a sense of our lost and undone state without an interest in the merits of Christ. It should be our greatest care to trust in the Lord, as David did, Psalm xxxi, 1. In thee O Lord I put my trust.[2]

In his Address to the Negroes of the State of New York (1787), he shared more of his views of salvation.

Now the Bible tells us that we are all by nature, sinners, that we are slaves to sin and Satan, and that unless we are converted, or born again, we must be miserable forever. Christ says, except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God, and all that do not see the kingdom of God must be in the kingdom of darkness. There are but two places where all go after death, white and black, rich and poor; those places are Heaven and Hell. Heaven is a place made for those who are born again, and who love God, and it is a place where they will be happy forever. Hell is a place made for those who hate God and are his enemies, and where they will be miserable to all eternity. Now you may think you are not enemies to God, and do not hate him, but if your heart has not been changed, and you have not become true Christians, you certainly are enemies to God, and have been opposed to him ever since you were born.[3]

Regarding Hammon’s concern for salvation in “An Evening Thought,” literary scholar Vernon Loggins remarked:

Like the spirituals, the poems of Jupiter Hammon were composed to be heard. There is evident in his verse that peculiar sense for sound which is the most distinguishing characteristic of Negro folk poetry, A word that appeals to his ear he uses over and over again, in order, it seems, to cast a spell with it. In An Evening Thought, the word salvation occurs in every three or four lines. Any impressionable sinners who might have heard Jupiter Hammon chant the poem when in the ecstasy of religious emotion no doubt went away to be haunted by the sound of the word salvation if not by the idea.[4]

Lonnell E. Johnson, whose career included roles as a pharmacist, poet, professor, pastor, and publisher, said the poem “offers an exuberant testimony of his close encounter with the Lord Jesus Christ. . . . The intensity of his life-altering ‘salvation experience’ so ‘rocked his world’ that he couldn’t keep his feelings to himself. The words seemed to overflow, erupting into a passionate song of praise from the depths of the soul of this extraordinary poet.”[5]

Literature blogger Shannah Brown described the text this way:

An Evening Thought by Jupiter Hammon illustrates how many slaves drew meaning from their existence through a deep and profound connection with a God. . . . Hammon makes it quite clear that the master of his life is Jesus Christ and Him alone. It is amazing how slave owners, while understanding the threat that teaching a slave to read and write possessed, did not have the foresight to see the even greater threat that slaves believing in God possessed. By “allowing” slaves to identify with a Creator, the slave masters had unwittingly allowed themselves to become dispossessed of their power and identification as master. The slave, once learning of their Creator, understood that their true ownership was that of God Himself. Understanding the slave’s identification with God, Jupiter Hammon’s work becomes a silent protest, an insertion of dissent, a break in the slave mentality.[6]

III. Tune

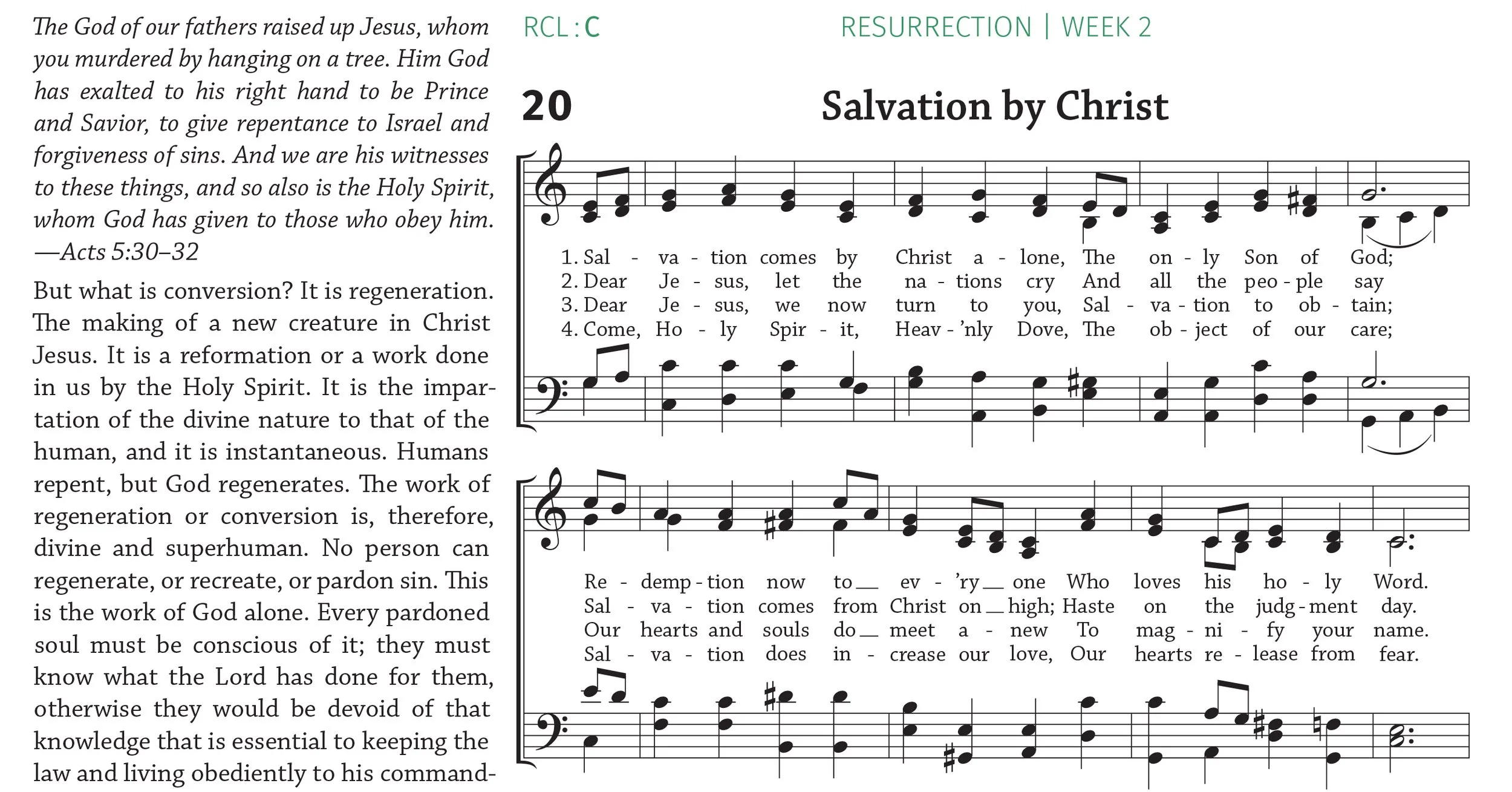

The first appearance of Jupiter Hammon’s poem in a hymnal was in Hymns & Devotions for Daily Worship: African American Edition (Louisville: Hymnology Archive, 2025), where it was set to a new tune composed for it by Raymond Wise, professor of music and African American studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. The new tune was named JUPITER in honor of the poet.

Fig. 2. Hymns & Devotions for Daily Worship: African American Ed. (Louisville: Hymnology Archive, 2025), excerpt.

Wise’s tune is written in a traditional chorale style, homophonic, with four quarter notes per bar, structured in antecedent and consequent phrases (alternating half and authentic cadences). The overall structure of abcb gives the tune some unity and aids its accessibility. There are some harmonic modernizations, including a C major chord over F at the end of the first bar, a B dominant 7, flat 9, at the end of the fifth bar (and thirteenth), a D9 in bar seven (and fifteen), and a C major chord over D in bar ten.

In describing his approach, Wise explained:

There is a particular sound in my head that I want to evoke when approaching the hymn from an African American gospel perspective. This sound does not always align with traditional hymn writing and voicing. For instance, I prefer closed voicing in certain sections and open voicing in others. I favor inversions rather than completely different chords in some places. Occasionally, I let the tenors soar at the top of the staff and into the ledger lines, but at other times, I want to keep them in a tessitura that works for the average singer. The use of parallel fifths does not concern me, as much gospel music moves in parallel thirds, fourths, and fifths. I enjoy certain awkward interval leaps, though not in every instance. Additionally, unison singing in some parts can be more powerful than four-part harmony. It may seem paradoxical, but this complexity contributes to the cultural distinctiveness of the music.[7]

For this edition, the text was edited to conform to the meter 8.6.8.6 D (CMD), and reduced to four stanzas, thus including eight quatrains from Hammon’s original text. The placement in the book is in relation to Acts 5:30–32 and its association in the Revised Common Lectionary with the second Sunday of Resurrection-tide. The devotion is an excerpt from the Autobiography, Sermons, Addresses, and Essays (1898) of Lucius H. Holsey, a mixed-race former slave, who at the time was bishop over the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church.

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

5 November 2025

Footnotes:

Cedrick May, ed., The Collected Works of Jupiter Hammon (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2017), p. 2.

Jupiter Hammon, A Winter Piece: Being a Serious Exhortation, with a Call to the Unconverted (Hartford, CT, 1782), p. 2.

Jupiter Hammon, An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York (Philadelphia: Daniel Humphreys, 1787), p. 10.

Vernon Loggins, The Negro Author, His Development in America to 1900 (Port Washington, NY, Kennikat Press, 1964), p. 12: Archive.org

Lonnell E. Johnson, “Celebrating Four Black Poets on Black Poetry Day,” Dr. J’s Apothecary Shoppe (17 Oct. 2017):

https://drlej.wordpress.com/tag/an-evening-thought/Shannah Brown, “Jupiter Hammon’s An Evening Thought: Finding identity through religion,” Art. Design. Literature. (8 Oct. 2014):

https://shannahbrown.wordpress.com/2014/10/08/jupiter-hammons-an-evening-thought-finding-identity-through-religion/Email from Raymond Wise, 24 June 2025.

Related Resources:

Jonathan Cohen, “A black poet’s view on Christmas, 1760,” The New York Times (25 Dec. 1977), pp. 9, 14.

Duncan F. Faherty, “Jupiter Hammon,” African American National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2013):

https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.34432

“Unpublished Jupiter Hammon Poem Discovered at New-York Historical,” The New York Historical (2015):

https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/jupiter-hammon-poem-discovered

Cedrick May, The Collected Works of Jupiter Hammon (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2017): Amazon

Viha Rosin, “Jupiter Hammon’s ‘An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries’: An Analysis,” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 23, No. 11, Ver. 2 (November 2018), pp. 24–26: https://www.iosrjournals.org

Chris Fenner, ed., Hymns & Devotions for Daily Worship: African American Ed. (Louisville: Hymnology Archive, 2025): website